In a recent SCA project I took a look at two of the more ubiquitous acetum preparations in modern herbals and attempted to trace them back in time to see how the stories told by herbalists stand up to scrutiny. Queen of Hungary’s Water was a rosemary distillation and bears little resemblance to modern preparation. The closest I’ve come to finding something that resembles fire cider is an Irish rheumatism cure that called for horseradish and mustard to be macerated in rum.

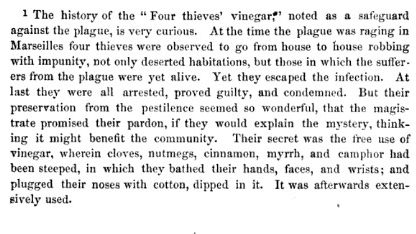

Four Thieves vinegar has some credence in terms of being at least somewhat verifiable. The story behind this preparation is mentioned in several medical books written in the 19th century.

I haven’t found any documentation of “thieves” part of the story. I think perhaps it is a bit of a 19th century herban legend. That’s the name I usually assign to historical stories invented by the herbalists who revived the herbal marketplace in the mid-20th century. All of them seemed to call for different aromatic herbs. Robert Hooper’s Lexicon Medicum shared the following receipt.

The Family Medicine Directory of 1854 shared the following receipt which looks a lot like the Acetum Aromaticum receipt from the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia (1817) which is attached to this post. What you will note is that not all of these receipts suggest internal use of the preparation. Some of them just talk about purifying the air with it. That’s very much a Richard Mead thing.

Putting the bit of Victorian whimsey aside, the use of these aromatic vinegars has a long history that undoubtedly predates written history. Hippocrates spoke of using rue, thyme, pennyroyal, and lavender in aromatic vinegar applications. Dioscórides wrote of using brine vinegar which is a mixture of salt and vinegar used to brine olives, infused with Creten thyme, barley groats, rue, and pennyroyal for driving out thick black humors.

Medieval physician Saladin Ferro suggested using a mixture of rosewater and an aromatic acetum for washing the nose and faces of people who had the plague in his treatise Concilium de Peste written in 1448. He also suggested sprinkling it around the room. This was later simplified into an acetum containing roses, rue, and wormwood which I still make and use today.

Making a Simple Acetum

Vinegar itself was considered to be a cooling preparation and most of our receipts specified the use of wine vinegar. Vinegar simples were made by macerating plants in vinegar.. Many of the Pharmacopeia of the 17th century included this receipt attributed to Mesuë the Elder. Mesuë was an Assyrian Christian who taught at the Academy of Gundishapur ca 800CE.

Vineger of Roses

Take of Rose buds (the whites being cut away, gathered in a cleer dry day, and dried in the shade three or four daies) one pound, Vineger eight sextaries, set them fourty daies in the Sun; then strain them, and keep the vineger, if you then put in fresh rose leaves, and set it in the Sun 40. daies longer it will have the better smell.

After the same manner is prepared Vineger of Elder flowers, Rosemary flowers, Sage flowers; Marigold flowers, Clove gilliflowers &c. let all the flowers be dried.

Yūḥannā Ibn Māsawayh (aka Mesuë the Elder) On Simple Aromatic Substances.

Culpeper shared some additional indications for using vinegar simples, by explaining that when using the same plant, wine decoctions are better than water decoctions for people who run cold. Vinegar infusions are better for people who run hot.

“They carry the same vertues with the flowers whereof they are made, only as we said of wines, that they were better for cold bodies than the bare simples whereof they are made, so are vinegers for hot bodies. Besides vinegars are often, nay most commonly used externally, viz. to bath the place.”[i]

People who need things “just right” would do best with a temperate preparation like an oxymel in which vinegar was cooked with honey to balance the qualitative properties. It seems as though perhaps aromatic vinegars were also thought to address this.

Physician Richard Mead explained the theory behind compounding aromatic vinegars was that combining the vinegar with aromatics eased the acidic effect of the vinegar on the stomach, while the cooling aspects of vinegar helped the aromatics from being too heating.

Wine Vinegar in small Quantities, rendered grateful to the Stomach by the Infusion of some such Ingredients as Gentian Root, Galangal, Zedoary, Juniper Berries, &c. Which Medicines by correcting the Vinegar, and taking off some ill Effects it might otherwise have upon the Stomach, will be of good Use: but these, and all other hot aromatic Drugs, though much recommended by Authors, if used alone, are most likely to do hurt by over-heating the Blood.[ii]

Richard Mead A Discourse on the Plague 1720

Mead had studied medicine at Padua and Oxford and taught at St. Thomas’ Hospital and Medical School. He was court physician to George I and George II and was commissioned by the crown to conduct a thorough investigation into the prevention and cure of plagues.

He’s definitely a valid primary source for the idea of preventing plague with aromatic vinegar. He was all about vinegar as an antiseptic for internal and external use. He is considered by some to be one of the first physicians to begin to understand germ theory as he believed the seeds of pestilence could be washed away and infected people should be isolated.

[i] Culpeper, Nicholas. Pharmacopoeia Londinensis: A Physicall Directory, or, A Translation of the London Dispensatory Made by the Colledge of Physicians in London. London, England: Printed for Peter Cole and are to be sold at his shop, 1649. https://archive.org/details/b30336879_0001.

[ii] Mead, Richard. A Discourse on the Plague. London, England: A. Millar, against Catherine St., 1744. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/32171/32171-h/32171-h.htm

References:

Beckmann, J. (1846 ). History of Inventions, Discoveries and Origins. London: Henry G Bohn.

Hartshorne, H. (1881). The Household Cyclopedia.Thomas Kelly.

Limbird, J. (1828). Four Thieves’ Vinegar. The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction.

Paris, J. A. (1825). Pharmacologia: corrected and extended…. Volume 2. New York: Samuel Wood & Son.

You must be logged in to post a comment.