There is a rich and varied history of Indigenous plant use in the Americas, but as you may know, I do not write about it. That is not my story to share. It is not my right to monetize another cultures’ knowledge. That would be appropriation.

The truth is that I couldn’t if I wanted to because I don’t use many native plants in my practice. My people brought their own plants and knowledge with them when they came to the US, and that’s what I learned growing up. When I do use native plants, I generally use it in the context of my culture.

For better or worse, that’s what Europeans have been doing for centuries. Between 1492 and 1607, European seafarers returned from the Americas with many new plants and other natural resources. Historians call this the Columbian Exchange due to the fact that European plants and animals were introduced to the Americas, as well. I’ve seen others call it the Columbian Extraction, but I don’t believe that sheds lights on the way European reshaped the landscapes they encountered.

Melons, cucumbers, gourds, squashes, zucchini, pumpkins, and luffas all belong to the diverse and useful plant family, Cucurbitaceae. There are cucurbits that are native to Africa, the Americas, and Europe.

Pumpkins (Cucurbita pepo) originated in Mesoamerica as toxic, bitter gourds bearing little resemblance to modern day pumpkins. They grew on the grazing pastures of mastodon. Seeds present in their dung indicate these gourds were a primary food source1. I think about this every time I see our local pumpkin farm letting their cattle out graze on the pumpkin fields.

Famine and scarcity caused by the decline of the megafauna likely led to the domestication of the plant. As far as researchers know this first started over 9000 years ago2when people living in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mexico began to eat the flesh of the gourds, saving the seeds of the biggest and most tasty for replanting. This went on for thousands of years resulting in our modern pumpkins.

It seems pumpkins were quickly introduced to Europeans. An early variety was painted on Queen Anne de Bretagne’s illustrated prayer book around 1503-1508.3 Large sun-ripened curcurbits of many varieties, including pumpkin, and the zuccha marina di chiogga were painted on the ceiling of Villa Farnesina between 1515 and 15184.

As I mentioned earlier, Europeans had sun ripened cucurbits they were already cooking with and using for medicine. The English called them gourds while the Italians called them zucche. When pumpkin came along, European chefs and physicans just used it like any other gourd.

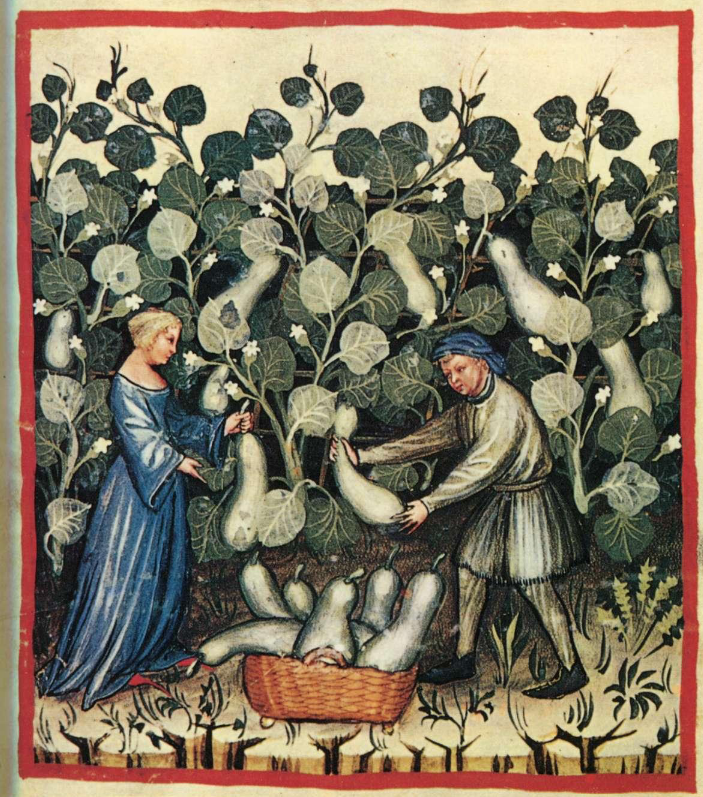

While Indigenous peoples in the Americas had their own methods of cooking the squashes native to their continent, the European appropriation and adaptation of these plants is what guided the way the earliest English colonizers used them. We are going to take a look at some of these old-world gourds and some recipes that predate the 16th century.

Medieval and early modern herbals often used imprecise terminology when describing plants. Terms like “gourd,” “melon,” and “cucumber” were sometimes applied interchangeably to different species of cucurbits, especially when botanical distinctions weren’t fully understood.

The most common variety that can be reasonably identified is Lagenaria siceraria (calabash) pictured above. It has a white flesh that they often “tinged with saffron” to make it yellow in dishes. The long, narrow, immature green fruit are still used for cooking in Siciliy where they call them cocuzzi. The shells of mature calabash fruits were used as lightweight, durable vessels,

Another interesting thing I have read about this plant is that Roman farmers insisted that taking seeds from the stylar end would produce rounder fruit suitable for making vessels while seeds from the peduncle end longer fruits for culinary use. So that’s a tip for you seed savers out there.

Cucumis melo is is often translated modernly as simply cucumber but it refers to the snake melon (today we see them called Armenian cucumbers) which native to the Mediterranean and also cooked into savory dishes.5

This final suggestion is highly questionable but it came up in a recent conversation so I thought I would share some conjecture.

Trichosanthes cucumerina (snake gourd) were also used for food6. Trichosanthes is the patola, written about in the Rig Veda. It’s possible you have heard this plant didn’t make it to Europe until the 17th century but seeds have been dated back to the Miocene and Pliocene in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland 7, so there’s a mystery here as to why it was not present in medieval cookery.

Snake gourd grows the same way that snake melon grows, producing slender fruits used in similar ways. It’s possible these two plants were categorized together based on these shared traits without distinguishing the species.

When the snake gourd ripens the inside contains a bright red pulp that can be used to make a sauces. At least one food historian I know thinks Apicus’ gourd sauce was made with this predecessor to tomatoes do to seeing similar sauces in African cuisine, but again this is just a wild theory I find interesting.

Cooking with Gourds

Most early recipes using gourds were savory pottages. Sugar was not widely available until after the Venetians discovered that it grew better in the Caribbean than it did in Sicily. Only the wealthiest of the wealthy could obtain sugar during the 12th and 13th centuries.

In Le Managier de Paris (1393) there is a recipe for fried gourd which I have made for SCA events with several kinds of winter squash including pumpkin and it is quite tasty.

Let the rind be peeled. for that is the best: and always if you want the insides, let the seed be removed, though it is said the rind is worth more, then cut up the rind in pieces, then parboil, then chop lengthways, then put to cook in beef fat: almost at the end yellow it with saffron.

In the Anonymous Tuscan Cookbook there are several ideas for preparing savory pottages that were made with zucche.

De le zucche

Cut and wash young zucche and dry them thoroughly with a cloth. Cook with fresh

pork, salt and saffron.

Clean and rinse the zucche as before and boil with diced hard boiled eggs, onions,

diced cheese, saffron and oil. Mix with minced meat to make raviolis or little pies.Clean and dry the zucche as before and soak in hot water until the evening when softened.

Dice finely with onions, pepper and saffron. Saute and toss with a civero sauce made with

with breadcrumbs and vinegar and bake. This dish can also be cooked with almond milk, pepper, saffron, salt and oil and walnut milkLibro della cocina Anonymous Tuscan (c 1380)

You can see in the following receipt that they had ways of preserving the gourds for future use.

CVII Tart of dried gourd

Take the (dried) gourd and boil it, then grind it well with lard, then put it into a bowl, add three drained cheese, pepper and saffron and make a paste and temper it with eggs and make the tart.Libro di cucina/ Libro per cuoco Anonymous Venetian c.1430

Pepon was the name given to sun-ripened cucurbits by the Romans. Paulus Aegineta wrote of the medicinal use of these gourds in his Medical Compendium written in 600 CE. Gourds were recommended as a remedy that was cooling, and moistening without astringency, along with henbane, endive, and horned poppy.8

The Tacuinum Sanitatis, a medieval handbook on health and well-being, categorizes various foods and their properties classifying foods like melons, cucumbers, and gourds as having cooling effects.

In a recipe in a 13th-century Andalusian cookbook the author advises the reader that a recipe containing the juice of roasted gourds and other cooling herbs and foods ” is given to feverish people as a food and takes the place of medicine.9” The Libre del Coch published in Spain in 1520 shares the following recipe:

Another Almond Dish for Invalids who have Great Heat and Great Burning

Cook a very tender gourd with water and salt until it is almost cooked; and then press it between two chopping blocks or silver plates, until the water comes out of them; and empty out the water in which they were cooked, and return them to the pot, and cast almond milk on them, little by little; and stir it constantly with a stick or spoon until the gourd is thick and quite mushy; and cast upon it a half ounce of sugar, stirring constantly; and cast on it a little rosewater to comfort the heart.

The concept of Semina Frigida Majora (Greater Cold Seeds) appears in various medieval and Renaissance medical texts, where the term describes a specific group of seeds including melon, citrul (watermelon), cucumber, and gourd.

This aligns with humoral theory, in which certain plants and substances were categorized based on their “temperaments” of hot, cold, dry, or moist. The seeds were prepared as emulsions meant to cool “hot” conditions.

European physicians working with this new species quickly assessed where it fit into their practice of humoral medicine. The energetic and medicinal properties of pumpkins were included in the many herbals that cropped at the end of the 1500s. so by looking at 16th century herbals, we get a good sense of how they incorporated the new plant into their system of medicine.

Pumpkin seeds replaced gourd seeds as one of the Greater Cold Seeds in the works of the Spanish missionaries who wrote the Badanius manuscripts and the Florentine Codex.10

In Lyte’s translation of Doeden’s Cruydenboeck (1554), he called all gourds pepones and mentioned the alternate name pompions for pumpkin, because he was not translating from Dutch but French and that was the name the French were using. That name actually hung on in England for quite a while.

Doedens classified the flesh as “colde and moyste” when cooked and recommended pounding strips of the flesh to apply to inflamed eyes. He also suggested pounding the seeds with barley meal and the juice of the plant and using this preparation to fade spots on the skin. (The English translation of Doedens is the herbal that Elder Brewster brought with him on the Mayflower.11)

And for the beautifying and making the skin smooth, vse the Oile drawne out of Pompion, or Citrull seeds, and of Pistaces…12

In 1573, Partridge included million seeds (and the other cold seeds mentioned above) in a formula meant to “restore strength in theme that are brought low with long sicknesse.”13.

In 1577, Thomas Hill wrote that the vegetable “profit the flegmatic and cholerick person” and had the ability to “clenseth the skinne, causeth Urine, purgeth the loynes, Kidneyes, and bladder, heale ulcers and cease speedy boyling.”14

In 1580, a physician Thomas Newton wrote that the pepon or million was “colde and moist in the second degree “useful for provoking urine and breaking stones.15

In 1597, physician John Gerard wrote about pumpkins in his herbal under the heading “Of Melons, or Pompions” later mentioning an English name “Millions16” His uses generally agreed with older texts saying the seed “is good for those that are troubled with the stone of the kidneys.” In addition, he suggested a pottage of the flesh simmered in milk and served with butter as a dish particularly beneficial to those with a “hot stomacke” and “inward parts inflamed.”17

This introduction of pumpkins into European humoral medicine in the 16th century illustrates how new botanical discoveries were integrated into pre-existing frameworks. Next we will discuss how an endearing classic food evolved.

Da Como’s zucca with almond milk, is generally credited with being the predecessor to our modern pumpkin pie because it has more sugar, but it’s more of a pudding than a pie.

Cooking pumpkins with almond milk

Cook the pumpkins in water, then drain as much water as you can, and sieve them or mash them through a holed spoon; now boil them with the milk and sugar, and with some agresto according to your master’s tastes.

Libro de Arte Coquinaria Martino da Como (1465)

I think people are too quick to call any recipe “the first” of anything. If you look long enough you will almost always contradict yourself.

Meat of the apples good and perfect. Take the apples, and peel and cut in quarters and let them boil; when they are enough cooked pour away the water, then put in the fat of the meat that you choose, and do in this way gourds also, and put good sweet spices and beaten eggs how it seems to you.

Libro di cucina/ Libro per cuoco Anonymous Venetian c.1430

The first recipe published in England titled To make a Pumpion Pye. was written in 1658. It was an intricate thing with pumpkin, apple and a wine caudle. Hannah Woolley published a bit simpler version in 1670.

To make a Pompion-Pie.

Having your Paste ready in your Pan, put in your Pompion pared and cut in thin slices, then fill up your Pie with sharp Apples, and a little Pepper, and a little salt, then close it, and bake it, then butter it, and serve it in hot to the Table.

The Queen-like Closet Hannah Woolley (1670)

Eventually they started leaving out the apple and the pies started to more closely resemble our modern pumpkin pies:

Tourte de citrouille. Tart of Pumpkin

Faites la boûitlîr avec de bon laiét , la passez dans une passoire fort épaisse , puis la meflez avec sucre , beurre , peu de sel, & si vous voulez un peu d’amandes diluée , que le tout soit fort delié ; mettez-le dans vostre abaisse , & la faites cuire ; eftant cuite , arrosea la la de sucre , & servez.

Boil it with good milk, pass it through a very strong sieve, then mix it with sugar, butter, a little salt, and if you want a little minced almonds, let everything be very fine; put it in your pie crust and cook it; Once cooked, sprinkle with sugar, & serve.Le vrai cuisinier françois François Pierre de La Varenne (1721)

In the late 18th century, we finally arrive at what are basically modern-day recipes for pumpkin pie.

Pompkin.

No. 1. One quart stewed and strained, 3 pints cream, 9 beaten eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg and ginger, laid into paste No. 7 or 3, and with a dough spur, cross and chequer it, and baked in dishes three quarters of an hour.

No. 2. One quart of milk, 1 pint pompkin, 4 eggs, molasses, allspice and ginger in a crust, bake 1 hour.

New American Cookery Amelia Simmons (1796)

Since the most common uses of the pumpkin today such as making pies and savory soups are European traditions, it seems fitting to close with my own family pumpkin pie recipe.

Golden syrup is going to give you the most traditional pumpkin pie, but I encourage you to play with the other sweeteners. My guess is that the malted barley syrup is the original ingredient in my family because they grew barley for making their moonshine.

Pumpkin/Sweet Potato Pie

2 cups pureed pumpkin or sweet potato

2 eggs

1/2 cup cream

3/4 cup golden syrup, malt syrup, maple syrup or molasses

2 Tblsp flour – I’ve made this gluten free by using rice or tapioca flour here.

1 tsp ground cinnamon

1/2 tsp nutmeg

1/2 tsp ground cloves

fresh ginger (optional)

- Preheat the oven to 375 degrees

- Line your pie tin with an unbaked pie crust.

- Mix all of the ingredients in the order given.

- Pour the filling into the crust.

- Bake at 375 degrees until a tester inserted in center of pie comes out clean, aproximately 40 – 50 minutes.

References

- Kistler L, Newsom LA, Ryan TM, Clarke AC, Smith BD, Perry GH. Gourds and squashes (Cucurbita spp.) adapted to megafaunal extinction and ecological anachronism through domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(49):15107–15112. ↩︎

- Decker, Dana. “Origins, Evolution and Systematics of Cucurbita Pepo (Curbitaceae).” Economic Botany 42, no. 1 (1988): 4–15. ↩︎

- Paris, H.S., Daunay, M.C. & Janick, J. (2006). First Known Image of Cucurbita in Europe, 1503–1508. Annals of Botany, 98(1), 41–47. ↩︎

- Janick J, Paris HS, Parrish DC. The Cucurbits of Mediterranean Antiquity: Identification of Taxa from Ancient Images and Descriptions. Annals of Botany. 2007;100(7):1441–1457. ↩︎

- Janeck Cucurbits of Mediterranean Antiquity ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Boer, Hugo J. de, Hanno Schaefer, Mats Thulin, and Susanne S. Renner. “Evolution and Loss of Long-Fringed Petals: A Case Study Using a Dated Phylogeny of the Snake Gourds, Trichosanthes (Cucurbitaceae).” BMC Evolutionary Biology 12, no. 1 (July 3, 2012): 108. ↩︎

- Aegineta, Paulus. Medical Compendium in Seven Books. Translated by Adams, Francis. 1847 Translation. Vol. II. London, England: Sydenham Soc., 600. pp 68. ↩︎

- Anon. Kitab al Tabikh Fi-l-Maghrib Wa-l-Andalus Fi `asr al-Muwahhidin, Limu’allif Majhul. Edited by Martinelli, Candida. Translated by Perry, Charles. 2012 Repring. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 1200. ↩︎

- Orta, Garcia de. Colloquies on the Simples & Drugs of India. Translated by Markham, Clements. 1913 Translation. London, England: Henry Sotheran and Co., 1563. 303. ↩︎

- Gifford, George. “Botanic Remedies in Colonial Massachusetts, 1620–1820.” In Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts. Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1978. https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/1215 ↩︎

- Guillemeau, Jacques. Child-Birth or, The Happy Deliuerie of Vvomen.., 1612. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A02362.0001.001. ↩︎

- Partridge, John, fl. The Treasurie of Commodious Conceits, & Hidden Secrets … Imprinted at London: By Richarde Iones, 1573., 1573. ↩︎

- Hill, Thomas. The Gardener’s Labyrinth. Translated by Mabey, Richard. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1577. ↩︎

- Newton, Thomas, Approoved Medicines and Cordiall Receiptes with the Natures, Qualities, and Operations of Sundry Samples. Very Commodious and Expedient for All That Are Studious of Such Knowledge. Imprinted at London: In Fleete-streete by Thomas Marshe, 1580. ↩︎

- Gerard, John. The Herball Or Generall Historie of Plantes. London, England: Norton, John, 1597. pp 775. ↩︎

- Gerard, 774.

↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.