While they aren’t the only sources, I pull from to write this blog I admit that I find the early manuscript receipt books particularly intriguing. We will be digging into individual entries in future posts, but for now I just want to paint them with broad strokes.

A few of the oldest handwritten manuscripts discovered so far include Collection of very special and unique confections and medicines of Madame la Duchesse d’Arscot (1533), Receipt Book of Lady Katherine Grey UPenn Ms. Codex 823 (1567) and A Booke of diuers Medecines, Broothes, Salues, Waters,Syroppes and Oyntementes by a Mrs. Corlyon (1606). A receipt book believed to belong to Venetia Stanley Digby (b1600 – d1633) contains many of the medicinal receipts that later were published in a book “authored” by her husband.

In some ways, the manuscripts remind me of the community cookbooks that used to be sold as fundraisers. In other ways, they remind me of the medicinal texts handed down in the Irish physician families. I think it’s fair to say they are indicative of a time when a great deal of medicinal preparation took place in the kitchen, and they illustrate the fact that the line between what was medicine and what was food was once not distinct.

Determining the authorship of these manuscripts is sometimes complicated. Sometimes there is no identifying information in the whole book. When we know the author, the receipts that have no identifying information are assumed to be theirs or a member of their household. Some books have entries that span hundreds of years written by several members of the family, such as the Fairfax family book.

Sometimes though the script can be misleading because families hired professional scribes to copy and index their books before passing them to the next generation. There are cases where a male scribe been given undue credit as is the case of Lady Borlase’s book which is credited to her scribe Robert Godfrey in the Szathmary collection.

To be fair, I must point out that some men also enjoyed collecting receipts and had their own books. I think it’s worth pointing out though those men usually left the domestic management of their homes to their wives or a housekeeper. One wonders if they had the insight the primary caregiver in the household did as to the efficacy of their cures?

The author of Le Managier de Paris begins that manuscript by telling his new wife that he only prepared his instructions for her because she was worried about her inexperience (she was 15) at managing a household. I have linked to a free translation of this manuscript, but it only transcribes the receipts. I recommend picking up Tania Bayard’s translation titled Medieval Home Companion to get an idea of the duties of the mistress of the home going into the early modern era.

People gathered receipts from a variety of sources. Some receipts came from acquaintances and others came from popular household manuals. Some receipts in the books were accredited to physicians.

Medical practice was very different. A physician might examine a patient in their home, recommend a certain formula, and leave it with the person in the home in charge of seeing that it was made, or purchased from an apothecary, and administered appropriately. The Dutch physician Jan Baptiste van Helmont explained the system like this:

Because Physitians will not be wise, but according to the custom of the Schools. For what they read, they believe, and what they believe, they deliver to the trust of the Apothecary, his Wife, and Servant or Family, to be put in execution. For thereby every maker or seller of Oyles or Ointments, and old Women, do thrust themselves into Medicine, scoffe at Physitians, because also, they oft-times excel them in many things.

Other times physicians didn’t even consult in person with their patients but sent letters back and forth in which the doctor would recommend a formula. This was very typical of professional healthcare at the time.

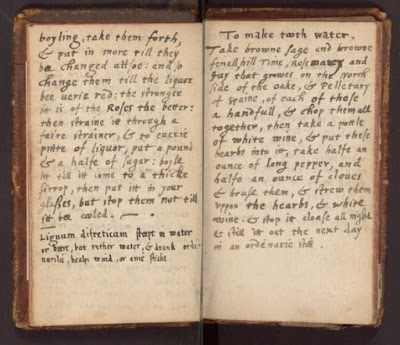

Source: Strachey, Elizabeth. “A Book of Receipts of All Sorts.” Somerset, England, 1693. HMD Collection. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

People shared those receipts amongst their friends both in person and via correspondence. We know this is how some remedies crossed the Atlantic. Dr. Edward Stafford of London sent a letter to Gov. John Winthrop of Boston in 1643 that contained several receipts that he might find useful for a flu outbreak in the colony1.

Receipts were also shared with the servants who worked in their gardens and still rooms so they could grow the herbs and make the preparation. That’s one way the knowledge passed back-and-forth between the classes.

Working as a still room maid for one of these women, was an opportunity for education and upward mobility. For example, the London chirurgeon Hannah Woolley was believed to have started her training working as a still maid for Ann, Lady Maynard. Woolley went on to author several books and became an advocate for the education of young women, insisting that women of all classes should be taught to read.2

Besides illustrating the skill-sharing networks that existed in early modern society, the attributions have helped us glean biographical information about the authors. For example, we know that Ann Fanshawe traveled with her husband because she collected new receipts from her time in Cork and Madrid. Some books have household inventories or other bits of information. Elizabeth Strachey’s receipt book attributes one of her receipts to her husband’s friend, John Locke. It’s a fascinating glimpse of another time.

Sadly, as women were pushed out of the professional sphere, we can observe the devaluation of this knowledge. Slowly the medicinal receipts vanished from the pages of cookery books. When The Receipt Book of Mrs. Ann Blencowe A.D. 1694 was published in 1925, the publisher, George Saintsbury was in awe of the “phisical” receipts in the manuscript.

Contrasting the book with modern cookbooks almost bereft of medicinal receipts he shared his “profound sense of inferiority to our ancestors” in regard to our capacity to care for our own health. 3 During Saintsbury’s time, most pharmaceutical medicines were still made from plants, so he at least had a healthy respect for Lady Blencowe’s receipts.

By 1998 when David Schoonover was editing Lady Borlase’s Receiptes Booke all he had to say in his introduction about her medicinal recommendations was that they were “laughable” but I’ve already let you know what I think of his commentary.

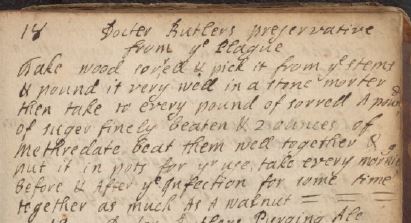

There are many ways that I could choose to relay the contents of these manuscripts to you. I could duplicate the actual words as they are written which is called diplomatic transcription. That’s still not really going to accomplish what I want to do with this blog, so most of the time I will show you a semi-diplomatic transcription and then provide modern directions with appropriate substitutions.

For those of you interested in looking at some of these books many libraries have collections so you just have to poke around. The Wellcome Library has a large selection, but many college libraries have a handful of these as well.

The handwriting can be a bit much for beginners to decipher so I will point you to a couple places where you can find transcribed documents.

Szathmary Culinary Manuscript Collection – I think the platform they use for doing transcription is poor and they aren’t done properly but this is the first project I worked on so I will share it.

Receipt Books at the Folger Shakespeare Library

References

- Stafford, Edward. Receipts to Cure Various Disorders for My Worthy Friend Mr. Winthrop, by Edward Stafford, 1643 May 6. Translated by Holmes. O.W. Vol. 1862 Reprint. Boston, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1643. and Kremers, E. “American Pharmaceutical Documents, 1643 to 1780,” Badger Pharmacist, no. 15 (1937). The original 1643 letter of Dr. Stafford is in the Boston Medical Library Collections, Countway Library. ↩︎

- Kamm, Josephine. Hope Deferred: Girls’ Education in English History. Methuen, 1965. (There are people who would roll their noses up at my use of the term chiurgeoto describe Woolley but that’s what she called herself and I respect self-identification.) ↩︎

- Blencowe, Ann. The Receipt Book of Mrs. Ann Blencowe A.D. 1694. Edited by Saintsbury, George. [1972 Reprint]. London: The Adelphi, Guy Chapman, 1925. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.