My original motivation for starting this project was to provide resources for people who had been to one of my workshops and wanted to research their personal cultural folkways. Everyone will have a different starting point, in this work. I grew up in a poor rural area in a family that still held strong associations with their cultural traditions.

If your family didn’t follow a lot of traditional practices like mine, you might be starting with just a general idea about where your people came from. You should consider yourself lucky if you know that much. Many people in the world had that taken away from them.

This work is going to involve some unlearning on your part. When I started my anthropology classes in college, I was sitting in a meeting of people who were going to work on a history project together. They knew I was friendly with a certain herbal author who wrote historical anecdotes in their books.

I spent an uncomfortable afternoon listening to them run through all the errors in one, as examples of mistakes we wanted to avoid. It was irritating, but it wasn’t paradigm-changing for me because I wasn’t invested in that truth. I already knew that the “history” in most herbal books is terrible. When I began attending herbal conferences, I bit my tongue about the way the history of herbalism was taught. I regret that now, but I wanted to make friends and often feel the need to mask in social circles to do that. No one likes the “well-actually” girl.

Most presenters who even gave a nod to historical practice were teaching the same male-dominated version of medical history handed down from the ivory tower or a neopagan-infused feminist fairy-tale.

Everyone was neglecting the wealth of knowledge that can be gleaned from a survey of medical texts and manuscripts written by women in various museum collections all over the world.

However, the reality is that the information in them directly contradicts a lot of lore thrown around in the Herbal Community™. I would not have written about this before I got old and crotchety enough that I don’t care about fitting in anymore.

The transcription projects I work on are important to me. Those manuscripts represent millennia of hands-on experience that should not be allowed to just fade away. They are more in keeping with what I learned growing up than anything I learned at those conferences.

I provide a lot of information on this website but I only write about my cultural influences because that’s my story. Because I know this work is challenging, I put together a few tips for you as you jump into researching your story.

Question Everything

Learn to recognize biases in presentation and translation. The documentation of history has always been in the hands of the learned elite who colluded with Power to make their culture THE consensual reality. History has been subject to revisionism by the patriarchy, people with nationalistic motives, second-wave feminists, and most recently neopagans and high school textbook publishers.

There will be contextual errors in things you read that are often tools of oppression. For example, if you see someone writing about “witchcraft” in Indigenous North American cultures understand that person is using a word that is not relevant to that culture and doesn’t accurately describe the practices. The innate fear of this word amongst Western European populations was used to justify land grabs and the displacement of Indigenous people. This is not the only time you will see me write about this.

Question Defined General Roles

The ‘his’story versus ‘her’story debate is inaccurate on both sides and there is almost always more complex nuance. ‘His’story books written are often mired in nationalistic or patriarchal nonsense while modern “herstory” is often based on a fertility goddess myth invented by the Victorians that might be more rooted in patriarchal nonsense than actual history.

If you have never considered the way the Maiden Mother Crone mythology categorizes the stages of women’s lives by their usefulness as breeders, it is worth thinking about. What is more irritating to me is how Victorian revisionism turned important gynecological herbs used by professional midwives into love charms and frivolity.

You will read that women weren’t allowed to own property in the early modern era but really very few people owned property back then. Most people rented from the gentry and in some places up to 15 % of the people leasing property were women. Widows usually retained their property until they died. Basically what I am saying is mortality rates being what they were, single-mother households are not unique to the last 100 years.

The whole “woman’s place is in the home” trope only pertained to wealthy women and even then it is not a complete picture. This belief is used by some to justify their stance that women belong in the home, but that does not stand up to a deep dive into history. Throughout history, poor women have had to work for a living. No woman in my family has ever been a housewife with no income. We’ve always had to do wage labor. Here are a couple of articles to get you thinking about that.

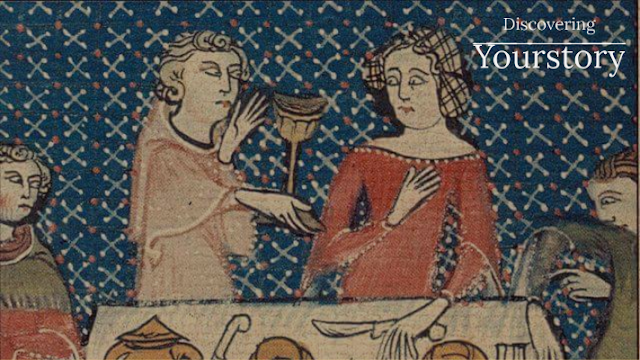

Medieval Women Were a Vital Part of the Workforce. We Can Learn from Them

Did Women Work In Agriculture?

Question Nationalistic Narratives

Romantic nationalism is a form of nation-building in which folklorists compile collections of narratives that bind the country together and create culture. This has perhaps the unintended effect of reinforcing the power of the state. The most well-known folklorists to do this were the Brothers Grimm in Germany. The English went on about their Anglo-Saxon heritage and so on.W.B. Yeats and other authors of the Celtic Twilight absolutely did this in Ireland.

Some researchers today are critical of “the leprechaunization of Irish prehistory” and “Celtic fakelore” while others embrace the green plastic hat fun as harmless. I wish I had known more about it when I started researching Gaelic herbal medicine decades ago. It would have saved me a good deal of backtracking and a bit of embarrassment.

Use Primary Sources Whenever Possible

I am sure some of you have seen those terrible formulaic “history” paragraphs at the beginning of scientific journal articles. Researchers who write medical journal articles are told writing that paragraph establishes plant medicine as a long-standing tradition and validates their research and they aren’t particularly concerned about accuracy.

I cannot count the times I have read one of those that started with something like, “Dioscórides says in his Materia Medica” and thought to myself, “No, he most certainly did not. Unfortunately, many researchers copy information gleaned from other secondary sources that inaccurately cite primary sources without fact-checking the quotes. If you are going to write about history, don’t pass erroneous attributions along to the next person.

To be fair, this was more difficult before the days of digitization, but these days the internet makes it easy to find primary source documents. There are ways around firewalls these days as more people in academia are recognizing that information should be freely available to all.

Don’t Rely Too Heavily on Expert Commentary

Don’t assume that just because someone has some letters behind their name you need to defer to them. I have had people with many more letters than me, argue with me that women were not allowed to teach at the Salernitan medical school and various women’s treatises on health were never published.

Some people are really invested in the version of history written from their viewpoint. I once had a professor who wouldn’t let me mention Louise Bourgeois in a paper because at the time there was no English translation of her work and he didn’t believe a woman wrote it.

Another example I have come across in my research is the commentary on the translations on the CELT database. In the lead-up to one translation, the linguist says that there is no reference found to yarrow in the Latin version of the medicinal work and therefore concludes it is a “uniquely Irish herb.”

That’s just not true. Pliny wrote that yarrow was the herb Homer mentioned in the Iliad. Archaeologists found yarrow amongst the medical supplies of a Roman ship that sank off the coast of Tuscany. The issue here is that the ancients called it milfoil or herbis militaris. The linguist who wrote that was clearly not grounded in plant history and probably should have kept their commentary focused on what they knew.

Use Reference Management Software

You are not going to remember everything you read. Keeping your research notes available in a way that can be searched quickly when you are too tired to remember, is useful. I use Zotero because it is free Opensource software that you can download to your computer where it stores things on your hard drive. Just remember to back that storage file up to the cloud every so often.

Canny, Nicholas P. ‘The Ideology of English Colonization: From Ireland to America’. The William and Mary Quarterly 30, no. 4 (October 1973): 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/1918596.

You must be logged in to post a comment.