My yarrow is in full bloom and so I thought now would be a suitable time to tell you the story of the Achillea nobilis that I now grow in my medicinal garden. Yarrow is one of the first plants my kids learned about. I am notoriously clumsy and often ended up cutting myself and sending them to the garden for some.

One of the things that people often ask is whether Achillea millefolium has always been the only “medicinal” yarrow, or if other species can be used. I decided to do some poking around and I was quite honestly surprised by the answers I found.

The use of A. millefolium as a wound healer was known throughout the ancient world. It also seems that they were aware of its anti-inflammatory actions being useful in other situations. Pliny wrote of it as being useful for seven remedies.

THE MILLEFOIJUM OR MYRIOPHYLLON; SEVEN REMEDIES.

The myriophyllon, by our people known as the “mille- folium” … is remarkably useful for the treatment of wounds. It is taken in vinegar for strangury, affections of the bladder, asthma, and falls with violence; it is extremely efficacious also for tooth-ache.[i]

The Romans also called it Herbis millitaris, likely due to its use by military physicians. A. millefolium was discovered in the medical supplies of a Roman ship sunk off the coast of Tuscany.[ii]

The 11th-century text Physica attributed to Hildegarde von Bingen, suggested tying warm yarrow to a wound as a poultice. She also mentions yarrow as a remedy for tertian fevers. Tertian fevers are now called intermittent fevers as they rise and drop cyclically. They can be associated with sepsis, various viruses, malaria, and various inflammatory diseases.

A person whom tertian fever torments should cook yarrow and twice as much female fern in sweet, good wine. He should strain this wine through a cloth and drink it at the onset of the fever.[iii]

In Middle English, yarrow was sometimes spelled Ȝarwe (that letter is yogh) which was eventually morphed into gearwe and then to yarrow. As a medicine, it shows up in Middle English manuscripts in the context of being a vulnerary (wound healing) and an anti-inflammatory.

For pe piles) Tak millefoyle i nofebledels or yarow, ſtampe hyt smal,[iv]

Many receipts in our early modern manuscripts suggest milfoil or yarrow for wound care. Its use as a hemorrhoid remedy also persisted. Those two uses come together in an interesting intersection in which it was used as an intervention for bloody flux or chronic diarrhea.

By the time Linnaeus classified the herb in the late 1700s, its use as a wound-healing herb was well established. Linnaeus named the herb after the Greek hero Achilles, Homer tells us that Achilles learned to heal wounds from the Centaur Chiron and passed the knowledge along to Patroclus. After being wounded in battle Eurypylus implored Patroclus, “Help me to my black ship, and cut out the arrow-head, and wash the dark blood from my thigh with warm water, and sprinkle soothing herbs with power to heal on my wound, whose use men say you learned from Achilles.”[iv]

I spent years firmly convinced that the terms Milfoil and Yarrow were the same plant. I think most people do. Then I came across the entry I mentioned above from Ein mittelenglische medizinbuch, and I had questions. So, I started looking for more. I found this entry that seemed to be speaking of two different plants.

“TAke a good handfull of Millfoyle or Yarrow, and poure on it in a fit Glasse a quart of very hot water, and so let it stand all night, in the morning drink a large draught, and so the rest the next morning, this continue for a moneth renewing it every other day.”[v]

I found another in Lady Catchmay’s book, and it absolutely cannot be disputed that she’s speaking of two plants here:

“A sure help for a green wound Take milfoil which is much like yarrow, bruise it well with a clean hand or a mortar, & put that in the wound or cut, & within five or six dressings it will heal & close, & to drink as much bugle stamped in a mortar, & tempered with wine, & then give it to the sick to drink.”[vi]

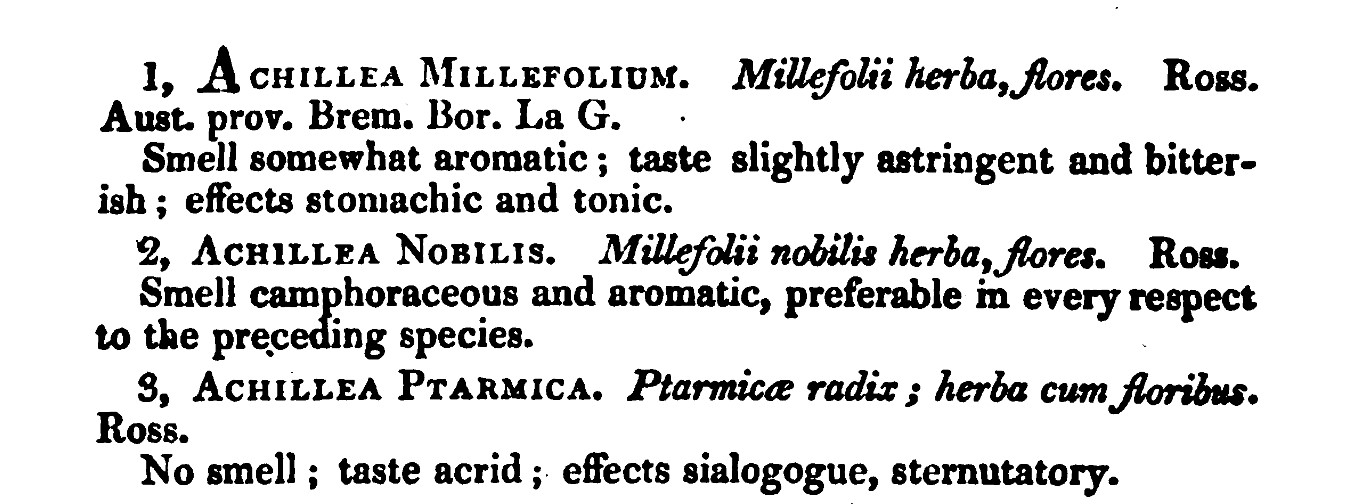

Then I found this:

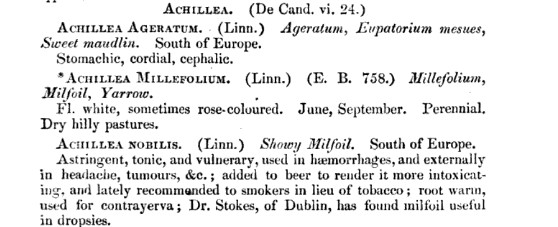

It’s not often that something surprises me, but I had no knowledge of this species. It seemingly disappeared from the medical books during the great standardization. It’s especially odd to me that some of the 19th-century linguists didn’t even seem to know about it when physicians were still writing about it.

I can state with reasonable certainty now that historically Milfoil and Yarrow were not always used interchangeably. Milfoil is Achillea millefolium and may also be yarrow, but yarrow may also refer to Achillea nobilis even in relatively modern literature.

Of course, you know once I knew this, I had to grow it. Finding the seeds was the first challenge. I have a guy, that I get my rare seeds from but he didn’t have these and I discovered a new source for buying seeds.

Yarrow is a perennial in zones 3-8. It isn’t fussy about its soil. It can handle a pH of anywhere from 6-8. It also doesn’t need great soil. In fact, it has been my experience that it is more aromatic when grown in poor soil. The only thing yarrow really doesn’t love is wet feet. You want to plant it somewhere dry. It sends down a long taproot, so you are going to want to make sure it has at least 12 inches of soil to grow in.

As far as sun requirements are concerned, I have experimented with planting it in different spots all over my garden. It will tolerate partial shade, but it prefers a lot of sunlight. I have decided that it grows straighter, taller, and blooms more prolifically, the more sun it gets. Planted in the same spot A. nobilis will have bigger blooms and more of them.

I’ve been growing A. millefolium for decades, this is my third year growing A. nobilis. I waited to talk about it until I had a feel for it, and I will have to tell you that I am going to agree with our Scottish friend up there that A. nobilis is preferable in every respect, except perhaps the astringency of the leaves. I don’t notice a dramatic difference in that respect. It’s far more aromatic and I finally understand why yarrow was used for toothaches. A. nobilis can be numbing if you overdo it.

So that’s just one of my little experiments that I thought I would pass along to you all. I hope you give it a go. There are many reasons for growing yarrow in your garden aside from wanting to experiment with its healing properties. Its aromatic blossoms attract many beneficial insects to your garden including ladybugs, hoverflies, parasitic wasps, and lacewings. It is also a favorite of black swallowtail butterflies. It is long-lasting in a cut flower bouquet, and it dries nicely, too.

Think about how you are planting it in relation to other plants in your garden. Yarrow is what we call in ecological design “a nurse plant” for areas experiencing drought. Its leaves and umbrella-like blooms shade plants that are more delicate and the thick leaves act like a living mulch holding water in the soil. I find A. nobilis to be more of an umbrella plant and A. millefolium to have denser foliage.

[i] Plin. Nat. 24.95

[ii] Institute for Preservation of Medical Tradition. 2010. “Research Breakthrough: 2000-year-old medicine revealed.” Institute for Preservation of Medical Tradition. September 23. Accessed June 5, 2015

[iii] Heinrich, Fritz. Ein mittelenglische medizinbuch. S, M. Niemeyer, 1896.

[iv] Hildegard, Saint. Hildegard Von Bingen’s Physica. Translated by Throop, Priscilla. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 1998.

[v] Talbot Aletheia. Natura Exentereta… Edited by Philiatros. (EEBO-TCP Phase 1). London, England: Printed for, and are to be sold by H. Twiford at his shop in Vine Court Middle Temple, G. Bedell at the Middel Temple gate Fleetstreet, and N. Ekins at the Gun neer the west-end of S. Pauls Church, 1655.

[vi] Catchmay, Lady Frances. ‘A Booke of Medicens’. Wellcome Collection, 1629. MS.184a.

You must be logged in to post a comment.