It seems that this blog is just going to be my avenue for answering questions that come up in meetings so I don’t go off on tangents. To begin this I want to say that the image above is slightly misleading as it is a picture of the collards growing in my garden. The short answer to the question is that colewort was a word used for all non-heading varieties of the Brassica oleracea cultivars.

At some point, all the brassicas in the modern diet were hybridized from the progenitor species Brassica oleracea. This plant is closely related to Brassica cretica which leads some people to believe B. oleracea is a version of this first brought to the British Isles, due to Roman expansion. This is one speculative paper written in 2021. There is no consensus despite what you might read on the internet.

It makes some sense though. The Greeks and Romans absolutely wrote about brassicas and colewort was listed in Charlemagne’s capitularies as one of the plants his subjects were required to grow on their estates, along with the potherbs chicory, pennyroyal, endive, savory, mints, tansy, beet greens, mallow, orach, lamb’s quarters and kohlrabi which is also a cultivar of B. oleracea.

My common sense theory is that people looked at two plants that were very similar and used them the same way, as happened later with cranberries, walnuts, and elder.

Regardless, Kew has identified that there is a Brassica oleracea native to coastal regions of England, France, and Spain. Further hybridization of this species is what led to plants like Brussels sprouts, broccoli, savoy cabbages, and cauliflower. Other brassicas are the result of further hybridization. For example, rapeseed (Brassica napus) is an ancient hybrid of turnip (Brassica rapa) and cabbage (B. oleracea var. capitata).

In Latin, caulis refers to the aerial part of all non-heading varieties of the Brassica oleracea cultivars while Culpeper said caulium refers to the root. This became cole or colys in Middle English.

There are several spelling variants of this word used for the leaves of early non-heading cultivars of the Brassica oleracea species including cole, cale, and so on. Some believe that the common name collard is derived from this word and for that reason believe that collard greens most closely resemble older cultivars.

It seems likely that it o believe it was used for several cultivars based on entries like one in Aletheia Talbot’s book that specified using “ Colewort with the jagged leaf” and Culpepers use of the plural Coleworts in his entries.

Medicinal Uses

Cole wort leaves are mentioned frequently in medicinal preparations included in our manuscript receipt books due to having been included in many medieval medical texts. In fact, they were so commonly used that Old Women who sold medicinal herbs on the streets of London, were said to be carrying cole baskets.

Many medical authors continued to use the Latin term. In the 14th century Chauliac wrote that “Caulis is a worte or cole hote in þe firste degre & drye in þe secounde; it matureþ & clenseth.” Culpeper was still using Caulis for brassicas in the 17th century. saying “Coleworts, or Cabbages garden and wild. They are drying and binding, help dimness of the sight, help the spleen, preserve from drunkennesse and help the evil effects of it.”

If you are aware of the history of midwifery at all the following receipt will probably seem most familiar to you. Many people share some “half of the story” kind of remedies using cabbage leaves for mastitis. I really prefer the darker, more bitter leaves over modern cabbage. I think it’s useless.

A medycyn for a woman that hathe a sore or swelling breste

Katherine Seymour Hertford 1567

Take a Coleworte leafe and cut awaye the vayne of hyt and then anoynte the leafe wth maye [clarified] Butter boyled wth Rose water and so laye yt to the sore brest and yt wylle swage the swelling.

Many of the uses seem to involve topical application to soothe inflammation.

A proved Medicine for a burning or scalding by lightning or otherwise.

Elizabeth Grey 1653

Take Hogs grease, or Sheeps Tallow, and Alehoofe (ground ivy, creeping charlie) beat these very well together, then take more Hogs grease, and boil it to a Salve.

To use it. Annoint the place grieved with this ointment, and then lay upon the sore so anointed Colewort leaves, which must be boyled very soft in water, and the strings made smooth, with beating them with a Pestel.

Modern Directions

- Make a salve with alehoof and lard in the manner I explain in my making a green salve post.

- Take collard leaves or kale leaves and simmer them until they are soft enough that you can flatten them, but they still hold their form.

- Apply the salve to the burned area and lay the leaf over top.

This is an interesting receipt that uses the juice of colewort leaves for binding a paste used to make pills for a headache.

Pils for the head XV

Take of Alloes a dram the rootes of wild gourds of all sorts, of Mirabilans, Diagredium, Masticke, Bayberries, Roses of each halfe a dramme of Saffron a Scruple stamp them well together with the Juice of Coleworths & take Seaven pills of the Same Morninge and Eveninge

Catherine Sedley 1686

Colewort was hybridized regionally into modern non-heading varieties like kale (Brassica oleracea var.acephala), lacinato kale (Brassica oleracea palmifolia), Tronchuda cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. costata) and modern collards (Brassica oleracea var. viridisis). While we don’t have the original species to work with anymore, any of these cultivars can and have been substituted for Colewort since the time these were written.

Cooking with Coles

By the time books of cookery started to emerge compact head-forming varieties had been refined and we see the use of the word caboche (also spelled cabache, caboge, cabage) and cole worts. This is a receipt that is typical of the pottages at the time that highlights cole wort.

Hare in Wortes.

Take Colys, and stripe hem faire fro the stalkes. Take Betus and Borage, auens, Violette, Malvis, parsle, betayn̄, pacience, þe white of the lekes, and þe croppe of þe netle; parboile, presse out the water, hew hem smaƚƚ, And do there-to mele. Take goode brotℏ of ffressℏ beef, or other goode flessℏ and mary bones; do it in a potte, set on þe fire; choppe the hare in peces, And, if þou wil, wassℏ hir in þe same brotℏ, and then̄ drawe it thorgℏ A streynour with the blode, And þen̄ put aƚƚ on̄ the fire. And if she be an̄ olde hare, lete hire boile weƚƚ, or þou cast in thi wortes; if she be yonge, cast in aƚƚ togidre at ones; And lete hem boyle til þei be ynogℏ, and ceson̄ hem witℏ salt. And serue hem forth.

And Here Begins a Book of Kookery written in 1430.

I’ve seen many recipes like this that recommended blanching a variety of pot-herbs. There were first blanched, strained, and then chopped up to be used to make pottages like this with oatmeal and meat.

Another common way to prepare them though was just to make buttered worts. I reckon this to be a recipe only used by people with some means, as it shows up in those kinds of cookery books.

This is the way I grew up eating collards so I will share modern directions for this receipt as well. If you can’t afford butter, you can substitute some kind of animal fat for the butter.

To mak buttered wortes tak good erbes and pik them and wesche them and shred them and boile them in watur put ther to clarified buttur a good quantite and when they be boiled salt them and let none otemele cum ther in then cutt whit bred thyn in dysshes and pour on the wort.

A Noble Boke off Cookry 1468

Modern Directions

1 lb collard greens

¼ cup butter

1 handful of white bread crumbs

Salt

Prepare the greens by washing them, removing the veins and stems, and chopping the remaining leaf. Some receipts will tell you to blanch or parboil the leaves and strain them before using. I always do this. It improves the flavor.

Place the leaves in a pot with boiling water and butter. Simmer until they are cooked to your liking. I cook them until most of the liquid is gone.

Serve over bread.

The receipt tells you to serve the greens on thin slices of bread. In my family, we just toss the cooked greens with a little bit of salt, pepper and whatever else strikes our fancy and sprinkle breadcrumbs on top. Then we pop them in the broiler for a minute until they get some color.

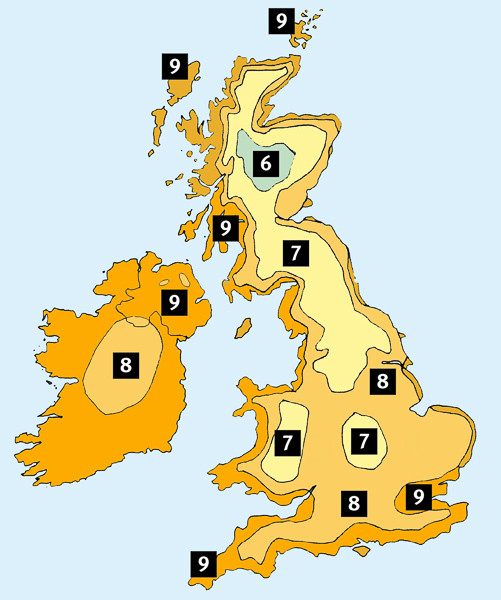

I think what makes the non-heading brassicas popular is accessibility. Many of these plants will keep producing all winter long, like crazy. In zone 8 and warmer collards often provide a harvest through the entire winter. Kale is common in traditional Scottish dishes and it was probably due to the fact that it could handle the cold temperature of the Highlands a bit better, staying green most of the year in zones 7 and warmer. It was commonly referred to as curly kale in the vernacular, probably to distinguish it from collards. Here is a map that frames the UK in terms of US hardiness zones so my readers from across the pond have a reference.

Colewort was brought to North America by the earliest English colonizers of Jamestown and further hybridization occurred. If you ever get a chance to visit the Cloisters garden in New York, they have what I believe is the earliest American hybrid growing in their pot-herb plot.

I push back against the idea that collards are uniquely Southern food though because I grew up in a northern family with no ties to the south and we ate them regularly using recipe I posted above. I tend to think they were something most rural poor folk knew about.

There’s an idea that they don’t grow well in the northern US states that I don’t quite understand. I live in US growing zone 5 and collards grow quite well here during our growing season as you can see in the picture up above. They do not grow all year. The average low temperature here is -10° to -20°F (-22° to -28°C) so like everything else in my garden, they will eventually winter kill. If I didn’t plant and preserve foods that don’t overwinter in Iowa, I would be a very hungry person in the winter months.

Collard greens became tied to Black cultural foodways in the American rural south -likely because of their accessibility and status as peasant food, but that is not really for me to say a lot about. Please see food historian Michael Twitty’s excellent post on this subject.

You must be logged in to post a comment.