We are going into cold and flu season and most likely will see a spike in Covid-19 cases as well so I want to take this time to really dig into what it means to care for the ill and convalescing and how that was done historically.

I like to start talking about a subject with posts that explain to you what is going on in your body, and with your emotions when you are ill. I already pulled in my post about the stages of illnesses from an integrative perspective and I encourage you to look at that as a starting point. In this post, I want to really dig into the physiology behind fever because it’s something a lot of people worry about.

Acute fevers are fevers of sudden onset that are less than seven days in duration and are typically associated with infection. They can be bacterial in etiology such as upper respiratory tract infections or urinary tract infections or viral infections like influenza, or COVID.

Fever is regulated by the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a part of the ventral brain just above below the thalamus and above the pituitary gland and produces the hormones that control many of your bodily functions including helping to keep your body temperature right around 37ºC (98.6ºF) plus or minus one degree.

When pathogens invade your body whether it is those that cause infectious diseases or those that might infect a serious wound like an abscess they release substances called pyrogens. These substances cause your cells to release various chemical signals in the form of small messenger peptides called cytokines such as IL-1 ß, IL-6, TNF, and interferon. You might also recognize these as mediators of inflammation.

These substances pathogens release are called exogenous pyrogens while the cytokines are called endogenous pyrogens when they act in their role to provoke fever. Endogenous pyrogens initiate a fever cascade which ends with the prostaglandin PGE2[i] communicating to EP3 receptors in the ventral medial preoptic (VMPO) area of hypothalamus.[ii] Cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors like aspirin and acetaminophen will reduce fevers by interfering with this cascade and lowering the amount of PGE2 that makes it to the hypothalamus.

It is believed that this area of the hypothalamus interprets signals from your body and initiates your body’s defense mechanisms. One of these actions may be to raise the set point for your body temperature. That means that it temporarily signals your body to increase your core body temperature. Your body has several mechanisms for generating heat and when the set point goes up, it activates them all.

You may feel chilled due to your body temperature being lower than the new set point. This perception signals your muscles to begin contracting to generate heat. This also drives the sickness behavior of wanting to cuddle up under the blankets to get warm and may cause some people to crave warm beverages.

The sympathetic nervous system is activated which stimulates thyroid release of thyroxines. Consequently, your metabolic rate increases significantly, 1 ºC rise in body temperature requires a 10–12.5% increase in metabolic rate.[iii] You may also notice that your skin is pale, and your hands and feet are cold because your body is directing heat towards your core.

This new core temperature is maintained by mechanisms that will promote adequate venting of heat including dilation of the blood vessels near the skin to vent heat which results in sweating. Fevers between 38° – 40° C (100.4° and 104° F) are a healthy expression of the immune system and do not require antipyretics.

They do change your body’s needs, though.

You require more oxygen so respiration rate and depth will increase heart rate as well. For every degree of fever that a person experiences, you can expect to see an increase of about 2.5 beats per minute in your pulse. This can make some people feel anxious.

Your body switches from using glucose for energy to using proteins and fat, so the rate at which your body consumes proteins increases. I believe this is the reason why meat broths such as beef tea were so popular as food for the ill.

The heat generated by all this metabolic activity enhances immune system function by increasing the motility and activity of white blood cells, stimulating interferon, and activating T cells required for producing the antibodies necessary to protect you against future infection. Heat also inhibits the growth of pathogens.

When the set point drops back down your fever breaks and you might crave things that will cool your body down, like cooling drinks. You might also crave carbs as your body makes the switch back to the parasympathetic state and burning glucose.

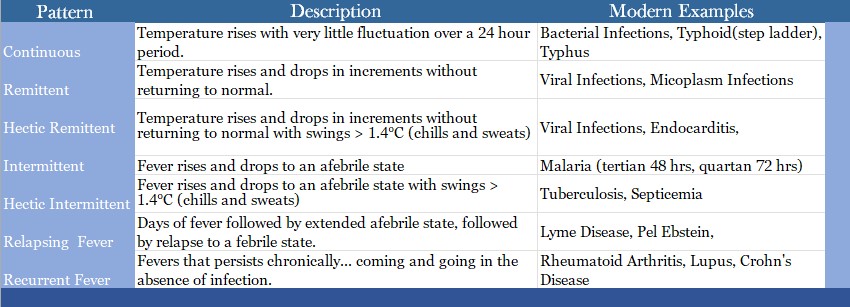

Fevers occur in various patterns. Modernly we know that certain pathogens provoke specific fever patterns because the fever spikes line up in some way with the lifecycle of the pathogen. For example, different families of Malaria parasites sometimes produce different patterns of intermittent fevers.

The following chart summarizes these patterns, but keep in mind this is not set in stone. I have three different physiology textbooks from college and each one of them explains things a bit differently. It is my own observation that bacterial infections tend to come with continuous fevers while viral infections tend to come with chills and sweats. There are exceptions of course, and some people have stronger immune responses than others.

Physicians once paid a good deal of attention to these patterns of presentation. They are defined by modern medicine but not used as much for diagnosis now that we have a greater understanding of the underlying causes of fever.

So let’s talk a bit about how our historic physicians viewed fever. Fever was generally attributed to one of the following causes:

1. Heat kindled by the spirits,

2. One or all of the humors becoming putrid

3. Inflammation in the body parts causing a hectic fever as explained below.

Humoral physicians believed that the change in the heart rate was because the heat of a fever originated in the heart. “For although a Fever may be kindled by the inflammation of other parts likewise, yet that happens not unless that heat first be sent to heart, and afterwards from thence to all parts of the body.[iv]

They had dozens of names for fevers. A phlegmatic fever was thought to be due to the putrefaction of phlegm. A sanguine fever was thought to be a fever engendered by bad blood and so on. It’s always interesting to me that they were kind of half-right about a lot of things.

There is one misunderstanding about terminology that I want to address. The term ague as used in the Middle Ages is derived from the Latin acuta, and meant hot fever or as Chauliac called it a sharp fever. During the early modern era, it became a more specific term for “fits” of chills that caused shivering and sometimes more intense muscle tremors called rigors that were associated with fevers.

I was suddenly surpris’d with a Chilness, and a Shivering, that came so unexpected, and increas’d so fast, that it was heightned into a downright Fit of an Ague, before I could satisfie my self what it was.

Occasional reflections upon several subiects Robert Boyle 1665

I have seen the term ague associated with the “fits” of fevers caused by the plague[v] and Hieronymus Brunschwig wrote, “ THe ague or feuer that taketh a man euerye daye is caused of Flegma when it falleth into the bloud and veines thēn doth the ague shake one and the colde is great.”[vi]

The paroxysm of malaria which is an episode of high fever, chills, and rigors that eventually breaks into a sweat is still defined as an ague. This leads many historians to call ague malaria every time they see the word but that is not the case.

I sometimes think the broader term persisted in folk use for a long time because no one has ever been able to make a convincing argument to me as to how Ma and Pa Ingalls contracted malaria on their isolated farm in Kansas, but I digress.

Early physicians had different protocols of treatment for each specific type of fever. Modern medical historians often look at fever remedies with the mindset of “Will this stop a fever?” If we do that we will find them lacking, because, of course, they won’t work like aspirin or ibuprofen.

In a way though that’s the beauty of these remedies. They aren’t going to put a fever out. They are going to let your body do what it needs to do. Diaphoretics, for example, work to support your body’s natural mechanisms to vent heat and maintain that new set point, by promoting peripheral vasodilation. They aren’t likely to lower a fever, much. They may be even more useful adjuncts for hyperthermia that occurs without a change in the body’s set point such as heat exhaustion because of how they work and we can investigate that.

When you look at historical remedies as measures that will take the edge off discomfort and meet some increased physiological and psychological needs, the older interventions are quite brilliant. Research has even shown that addressing fever meets certain psychological needs of the caregiver who may feel an intense need to do something proactive. [vii] I will be talking about these remedies more specifically in future posts.

[i] You might recall I talked about prostaglandins in my post on reproductive physiology.

[ii] The entire process for those who are interested is theorized to look like this Bacteria and Viruses>>> IL-1 ß, IL-6, TNF, and interferon>>>phospholipid A from cell walls >>> arachidonic acid (AA) by phospholipase A2 (PLA2). AA >>> PGH2 via cyclooxygenase (COX) >>> PGE2 by PGE synthase. PGE2 >>>EP3 receptor. COX inhibitors are used to stop this process and break fevers.

[iii]Evans SS, Repasky EA, Fisher DT. Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2015;15(6):335-349. doi:10.1038/nri3843

[iv] Sennert, Daniel. Nine Books of Physick and Chirurgery. Written by … Dr. Sennertus. The First Five Being His Institutions of the Whole Body of Physick: The Other Four of Fevers and Agues, Etc. (Made English by N. D. B. P.). J. M. for Lodowick Lloyd, 1658. Sennert was a prominent physician in the early modern era. He was a professor of medicine at the University of Wittenberg for 45 years. It has always been interesting how very close to accuracy this statement is if you just replace heart with brain.

[v] Edwards. A Treatise Concerning the Plague and the Pox Discovering as Well the Meanes How to Preserve from the Danger of These Infectious Contagions, as Also How to Cure Those Which Are Infected with Either of Them. London, England: Dawson, Gertrude, 1653.

[vi] Brunschwig, Hieronymus. A Most Excellent and Perfecte Homish Apothecarye or Homely Physik Booke, for All the Grefes and Diseases of the Bodye. Translated by Hollybush, Ihon. Imprinted at Collen: By [the heirs of] Arnold Birckman, 1561.

[vii] Ravanipour, Maryam, Sherafat Akaberian, and Gissou Hatami. ‘Mothers’ Perceptions of Fever in Children’. Journal of Education and Health Promotion 3 (28 August 2014): 97. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.139679.

You must be logged in to post a comment.