This will be the last of my posts on holiday traditions before we get back to business. I was recently inspired to do one of my deep dives and discover a bit more about the term “wassail.” I found out that even though I had read a lot about this, I was still mistaken about a couple of things. As usual my original misconceptions came from reading too many secondary sources on the topic. This time I limited myself to primary sources.

History is layered like a cake. The books written by the learned elite only tell the story of the top layer that is decorated prettily and experiences life quite differently than bottom layer whose existence is mostly hidden but supports rest of the cake. The way the wealthy and the poor lived has always been drastically different. The history of wassailing is an opportunity for me to talk about that. I am sure long-time readers know that I rarely pass those up.

I should point out I am only talking about wassailing in the sense of the home visiting, not the orchard visiting. I can’t find any primary source documentation about the orchard visiting practice that was written before those whacky, whimsical Victorians wrote about it and I am not willing to risk my reputation based on conjecture. It annoys me when anything like that is stated as fact because the truth of the matter is that we know next to nothing about pre-Christian practices in Ireland or the British Isles. We can only conjecture that this practice is a remnant of an ancient practice. Maybe it is a leftover remnant of Pomona’s Feast, although that was August 13th, but I cannot say for sure.

Wassaille! Wassaylle!

We will begin by paraphrasing Geoffry of Monmouth’s story of King Vortigern marrying Rowen the daughter of Hengist. Hengist held a feast to honor Vortigern during which his daughter Rowen, “came out of her chamber bearing a golden cup full of wine, with which she approached the king, and making a low courtesy, said to him, “Laueerd king wacht heil!” The king who was much taken with her asked his interpreter what she had said and was told “She called you ‘lord king’ and offered to drink to your health. Your answer to her must be, Drinc heil!” Geoffrey tells us that “from that time to this, it has been the custom in Britain, that he who drinks to anyone says “Wach heil!” and he that pledges him, answers “Drink heil!”1 Robert Mannyng told a similar version of the story 1338, although there was more kissing in his version.2

This is in keeping with the entry in the The Oxford Companion to Food which says the term comes from the Old Norse ves heill and Old English wes hal, meaning “be of good health” or “be of good fortune.”3

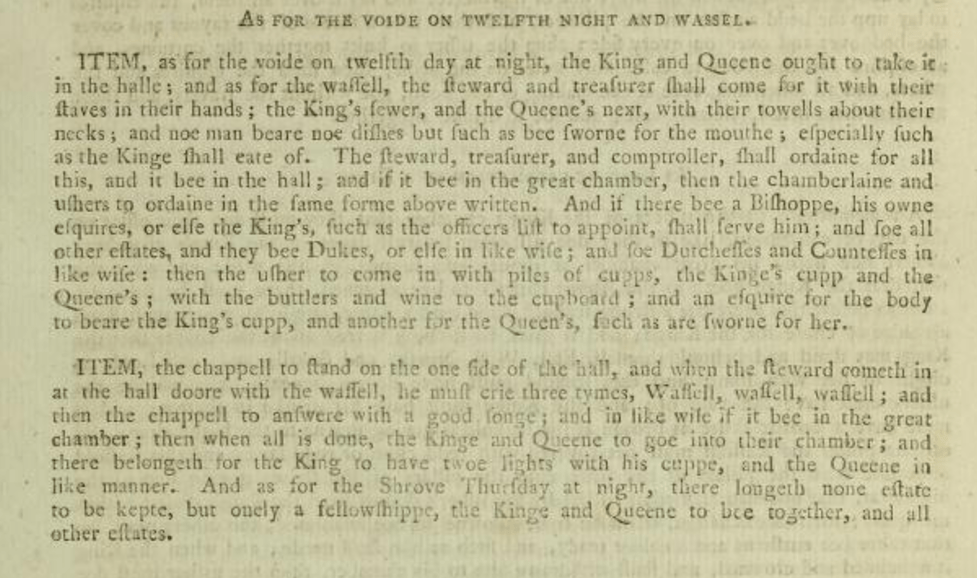

Wassail is simply an English way of saying “to your health”, like the Irish sláinte. Wassailing is an action word meaning to toast a person’s health. The wassail bowl is a bowl with which you offer this toast. At various points in history, wassailing has been associated with the winter holidays Christmas, New Year’s, or Twelfth Night, depending on which celebration was in vogue at the time. One of the best explanations we have of medieval practice is the following from Henry VII’s ordinances. (1494)4

This is the way the wealthy experienced wassailing. They raised toasts to one another, drank from the wassail bowl and sang songs, all in the comfort of their own home. Since this was after the Norman invasion of 1066, these cups raised to the King and Queen were likely wooden drinking bowls which were sometimes called mazers.5 Mazers could look like bowls as in the image above, or they might have a raised foot as in the picture below.

In a play written by Ben Jonson in 1616 Christmas’ daughter Wassell was described “bearing a browne bowle, drest with Ribbands, and Rosemarie before her.”6 Like everything wassail bowls belonging to the wealthy became increasingly elaborate. Eventually the custom became such that wealthy families might own a large ornate wassail bowl, inlaid with silver or ivory.

It’s Door-to-Door For the Poor

Poorer folk didn’t have the means to observe holiday traditions in such an elaborate manner as landowners. In fact, they were often required to supply their lords with extra goods for their holiday celebrations. The holiday celebrations of the peasantry depended on the charity of the wealthy.

Even after the feudal system was replaced by manorialism, poorer tenants went door-to-door in order to coax some sort of gift (ale, money, cake) from those who were comfortably enjoying their indoor celebrations. This is the origin story of all the old mumming/wassailing traditions. You can read more about that here.

Smaller wood mazers are believed to be associated with going door-to-door. Wood seems like a practical choice for something that was to be carried around while people were getting sloshed, but probably not everyone could afford cups as nice as these.

This jump from Twelfth Night to New Year’s makes sense if you think about it in the context of what was going on politically at the time. Keeping Christmas was frowned upon by Puritans. Cromwell enacted legislation in 1656 that allowed patrols to seize traditional Christmas fare, so many traditions jumped from Christmas to New Year’s at this point. Later you will find the Victorians writing of it as a Christmas Eve tradition.

Of course like everything there were many regional difference in the practice. It seems some wassailers carried ale and exchanged it for coins while others asked their wealthy neighbors to fill their empty cup with ale.

In 1648, Robert Herrick published two poems concerning wassail.7 I think it’s interesting that people often quote the poem that supports their thesis and ignore the one that doesn’t. “Twelfe night, or King and Queene” describes the ceremony as observed by householders of means who stayed home and toasted their guests health in much the same way the Tudors wasseled their king and Queen.

Herricks poem “The Wassaile” ends by foretelling bad luck for the household that fails to supply those blessing the house with ale or beer saying, “Alas! we blesse, but see none here, That brings us either Ale or Beere; In a drie-house all things are neere.

Not all the wealthy seemed to enjoy that obligation. 48 years later John Seldon spoke of wassailing as a New Year’s tradition saying, ” Wenches do by their Wassels at New-years-tide, they present you with a Cup, and you must drink of a slabby stuff; but the meaning is, you must give them Moneys, ten times more than it is worth.”8

In 1777, John Brand also described it as a New Year’s tradition. “Young Women went about with a Wassail bowl, that is, a Bowl of spiced Ale on New Year’s Eve, with some Sort of Verses that were sung by them in going about from Door to Door…be in Health. They accepted little Presents from the Houses they stopped at10. “

This jump from Twelfth Night to New Year’s makes sense if you think about it in the context of what was going on politically at the time. Keeping Christmas was frowned upon by Puritans. Cromwell enacted legislation in 1656 that allowed patrols to seize traditional Christmas fare, so many traditions jumped from Christmas to New Year’s at this point. Later you will find the Victorians writing of it as a Christmas Eve tradition.

Receipts for the Wassail Bowl

It does seem likely that prior to the 20th century the drink you were likely to find in the wassail bowl was a spiced ale that may or may not be fortified with brandy or sherry. There were several types of spiced ale that were common in the early modern era and it’s conceivable that any of them could have made it into the wassail bowl.

Mulled Beverages

If you are the type of person who pokes around in very old manuscripts, you might see the term moldeale referring to spiced ale. Some medieval scholars have written that the term mulling spices originated from the term mullyn meaning “to breke to powder, or mulle” and so they believed mulling to be equivalent to spicing a beverage.

That seems to be part of it. I have never found a receipt for mulled ale or wine that didn’t call for spices. But I also found mull defined as “to warm and sweeten wine or ale” in three different dictionaries published in the late 1700s including Entick’s, Walker’s and Perry’s. So heating and adding sugar seem to be part of the process as well.

Not everyone who wrote receipt books knew what they were talking about and occasionally you will find an error. Unfortuately if one 18th century cook mistakenly defines mulling as the process of pouring a drink back and forth between cups to froth it like you see in some early modern posset receipts, and one food blogger gets ahold of that error…well you all know how the interwebz works. This is why you have to fact check everything you read.

I am going to be generous here and say that although I’ve not come across any primary sources talking about mulled wine or mead in a wassail bowl, it is possible that someone might have used it. I have a theory about why they used ale,. which is somewhat supported by something Richard Cook says in Oxford Night Caps (1835). Ale was cheaper than wine or mead. According to Cook, Beer Flip was given to servants at Christmas and other holidays in place of a similar drink made with wine.10 If you knew a lot of people were going to come looking for drinks, you use the cheapest beverage you could to make it.

Flip

A spiced ale that was fortified with brandy called flip was popular with sailors. The oldest receipt I have found for flip so far is from 1695.

To make Punch or Flip.

Take a Quart of Spring Water, half a Pint of Brandy, a little Nutmeg and Sugar, and a little Lime-Juice, or a Lemon, or Verjuice, and squeeze into it; mix them well together, and its done.

For Flip 2 Quarts of good Ale or Beer, half a Pint of Brandy, a little Lemmon-juice, Nutmeg and Sugar mixt together, and it’s done. You may make either sort Stronger, by adding more Brandy, or Weaker by putting more Water, or Small Beer to them. Verjuice is as good as Lemmons, or better. Strain your Punch, or Flip through a Flannel Bag, and it will be very clear and Fine.

James Lightbody Every Man His own Gauger 1695

Mum

Mum is brewed with wheat, malt, and beans and tunned with spices including fir, birch and a common spices including elderflower, cardamom, thyme and barberry. You can find a receipt in Gervase Markham’s The Husbandman’s Jewel.

I have always been curious about this spiced ale simply because of the similarity of the name and that of the tradition of mumming. Of course the name might also be due to the amount of “cardomum” in the receipt. Someday I am going to make my partner (he’s the brewer) work out a manageable receipt for this and try it.

Lambs Wool

Going into this I would have told you that lambswool was ”the” wassailing beverage. After doing this dive, I would not. I have looked far and wide for 17th century receipts that supposedly exist other than Herrick’s and haven’t found one.

There are a few 19th century references about November 1st being dedicated to the angel responsible for looking over fruit and seeds called La Mas Ubal and lambswool being some sort of corruption. The story seems to have started with our friend Richard Cook. I’ve run several database searches for the term previous to 1825 and can’t find it. There are angels called the eralim (aralim, arelim, erellim) who live in the fourth heaven and govern over grasses, fruits and grains, but I have yet to find any corroboration that November 1st had anything to do with them. As I am about all things heathen, I will keep looking and update you if I find it.

If you look at the poem Herrick is giving you a list of things to put in the bowl lambs wooll, sugar, nutmeg, ginger and a “store of ale too.” I believe lambs wooll could be a name given to the roasted apple mash that you put in the bowl, but that is just conjecture on my part based on the fact that the practice persists in East Tennessee where some of my husband’s family is from. See Sidney Saylor Farr’s cookbook published by the University of Pittsburgh, More Than Moonshine if you need corroboration.

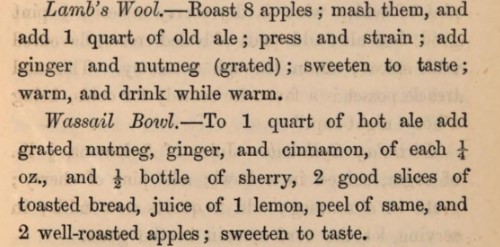

I am going to leave you with scans of two 19th century cookbooks that publish receipts for both Lamb’s Wool and another recipe for the Wassail bowl. If you are feeling adventuresome, you could give either a try. I actually like lambswool enough to make it with non-alcoholic beer, although I leave out the ginger. It’s nice to be able to offer visitors who don’t imbibe a reasonably authentic experience.

References:

- Geoffrey of Monmouth. History of the Kings of Britain. Edited by J A Giles. Translated by Aaron Thompson. 1999 Translation. Ontario, Canada: In parentheses Publications, 1135. ↩︎

- Mannyng, R. The Story of England, 1338.http://name.umdl.umich.edu/AHB1379.0001.001. ↩︎

- Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: OUP Oxford, 2006. ↩︎

- Society of Antiquaries of London. A Collection of Ordinances and Regulations for the Government of the Royal Household, Made in Divers Reigns : From King Edward III to King William and Queen Mary, Also Receipts in Ancient Cookery. London: England: London : Printed for the Society of Antiquaries by John Nichols, sold by Messieurs White and Son, Robson, Leigh and Sotheby, Browne, and Egerton’s, 1790. http://archive.org/details/collectionofordi00soci. ↩︎

- Hope, W. H. St John. ‘XI.—On the English Medieval Drinking Bowls Called Mazers’. Archaeologia 50, no. 1 (January 1887): 129–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900005592. ↩︎

- Jonson, Ben. The Vvorkes of Beniamin Ionson. The Second Volume.: Containing These Playes, Viz. 1 Bartholomew Fayre. 2 The Staple of Newes. 3 The Divell Is an Asse. 2011 December (TCP phase 2). London, England: Printed [by John Beale, James Dawson, Bernard Alsop and Thomas Fawcet] for Richard Meighen. 1640. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A72473.0001.001. ↩︎

- Herrick, Robert. Hesperides, or, The Works Both Humane & Divine of Robert Herrick, Esq. 2003rd-01 (EEBO-TCP Phase 1). ed. London, England: Printed for John Williams and Francis Eglesfield, 1648. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A43441.0001.001. ↩︎

- Selden, John. Table-Talk, Being Discourses of John Seldon, Esq or His Sense of Various Matters of Weight and High Consequence, Relating Especially to Religion and State. 2005th-03 (EEBO-TCP Phase 1). ed. London, England: Printed for Jacob Tonson … and Awnsham and John Churchill, 1696. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/A59095.0001.001. ↩︎

- Brand, John. Observations on Popular Antiquities: Including the Whole of Mr. Bourne’s Antiquitates Vulgares, with Addenda to Every Chapter of That Work: As Also, an Appendix, Containing Such Articles on the Subject, as Have Been Omitted by That Author. By John Brand, … Newcastle-upon:Tyne: Printed by T. Saint, for J. Johnson., 1777. http://name.umdl.umich.edu/004895859.0001.000. ↩︎

- Cook, Richard. Oxford Night Caps: Being a Collection of Receipt for Making Various Beverages Used in the University. Oxford, England: Longman and Co., 1835. https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1835-Oxford-night-cap-s. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.