A few weeks ago a person asked me the very valid question, “How did urban dwellers acquire all these fresh plants you talk about?

I have to admit that since I tend to turn my nose up at commodification and capitalism, I’ve kind of ignored this topic in favor of people who grew their own herbs. Being my own supplier makes herbs affordable and easy for me to access. Some people, however, don’t like digging in the dirt, and there have always been people who made their living doing it for them. Poor rural folk have always had to have multiple streams of income to sustain themselves, one of which was harvesting herbs in in the countryside and filling their “cole baskets” with herbs to sell at faires and on market days.

So in this post, we will talk about the gardeners and the merchants who supplied Western Europeans with their fresh plants….

Medicinal plants were highly commercially relevant at the time, and so it was sensible for schools and urban landowners to emulate the monastic gardens of medieval Europe on their private property.During the early modern period, European botanists established huge botanical gardens (hortus botanicus) where they taught. As botany and medicine were almost synonymous during this era, most had a dedicated area called the hortis medicus for the growing of medicinal plants.

Professor Luca Ghini established the first of these early modern botanical gardens in Pisa in 1543 and the expansive Università di Pisa Herbarium at Bologna a few years later. Orto Botanico di Padova was established by the Benedictine monks of St. Justina in 1545. It is the oldest university botanical garden that still stands in the same spot it was founded, today.

The University of Pisa Orto Botanico was moved in 1591. The Universität Leipzig’s botanical garden was officially dedicated in a spot where there had been a garden in 1580 and six years later the Botanischer Garten Jena was established.

Henri IV of Navarre founded the Jardin des plantes de Montpellier in 1595 because French students were going to Italy to study medicine at Orto Botanico di Padova. The professor in charge of Montpellier, Guillaume Rondelet, was the teacher of Matthias de l’Obel, Jean Bauhin, Felix Platter, Leonhardt Fuchs, Conrad Gesner, Laurent Joubert, and Charles de L’Écluse (Clusius). This list should astound students of medical history.

The Royal College of Physicians of London established a small teaching garden in 1614, but it wasn’t until 1670 that the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh was established near Holyrood Palace, as a teaching garden for their medical school. It was around this time that Kew Park, the forerunner to the Kew Gardens, was established as a private garden. Kew Palace also has a beautiful kitchen garden.

The Apothecaries Garden which later became known as the Chelsea Physic Garden was established in London by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in 1673, for the sole purpose of supplying apothecaries with those medicinal plants that could be grown in the English climate. In Ireland, the first Trinity College Physic Garden was established in 1687.

Not all notable physic gardens were associated with universities. Some were private botanical gardens like Conrad Gessner’s Alter Botanischer Garten in Zurick. Carolus Clusius was tasked with starting an imperial physick garden in Vienna before moving on to establish the hortus botanicus near the University of Leiden in 1577.

Jardin des Simples established by Jean Robin in 1597, was the first garden used by the University of Paris. Most plants from this garden were moved to Jardin Royal des Plantes Médicinales (Jardin de Roi) beginning in 1624 and Robin’s son Vespasian presided as their botanical lecturer until 1662.

Most wealthy people in London had gardens. Some people made a living planning gardens and writing books about botany and medical use called herbals. The Barber-Surgeon and herbarist, John Gerard Lord, curated Lord Burghley’s gardens at Cecil House, in The Strand, and at Theobalds House, in Hertfordshire.”1 Gerard’s own large garden was located near Fetter Lane while his competitor John Parkinson’s huge botanical garden was in Covent Garden.

Read more about London’s Botanic Gardens..

Foraging and marketing herbs is a profession that dates all the way back to the Greek Rhizotomoi “root-cutter” (ῥίζα meaning root + -τομος which indicates that cutting the roots was a profession) and the Roman Herbarii or “dealers in herbs.”2 Since I have been somewhat neglectful of them I will end this by focusing on the simplers.

The Rhizotomoi kept their knowledge of therapeutic plants, and the location of their sources, secret aside from training the next generation. Greek empirics like Dioscorides learned about the medicines that other practitioners purchased and used through interactions with the Rhizotomoi.

If you have read my other posts you know that I posit that the Greek schools of medicine spent a lot of time inventing some theories about why empiric methods were successful. I am more certain of that than ever having finally got my hands on an English translation of On Simples as attributed to Dioscorides.

These theories that came out of the Dogmatic school form the basis of early modern humoral medicine. Since because humoral medicine is mostly nonsense this led to even more theorizing and the formation of various schools of medicine whose members were pretty intractable when it came to medical theory. The Dutch physician Jan Baptiste van Helmont was pretty outspoken about the state of things in the late 1500.

Because Physitians will not be wise, but according to the custom of the Schools. For what they read, they believe, and what they believe, they deliver to the trust of the Apothecary, his Wife, and Servant or Family, to be put in execution. For thereby every maker or seller of Oyles or Ointments, and old Women, do thrust themselves into Medicine, scoffe at Physitians, because also, they oft-times excel them in many things.3

For this post I am not so much concerned about the squabbles amongst practitioners as I am with the way Van Helmont acknowledges that there were old women “thrusting themselves into medicine.” I am not sure if the term “old woman” was a honorific or if it just so happened that most of these people were, in fact, old women and professionals were using the words derisively.

Whatever the reason, the term is used in this context a lot. I first heard the term in a folk tune that talked about old women having been pressed into service to the crown, traveling with the armies and nursing wounded soldiers.

Older rural women often raised their families without being able to afford much assistance from physicians and consequently amassed a good deal of practical experience. Many of them also made a bit of extra money harvesting herbes in the countryside.4 Agrippa, who enjoyed poking at the establishment, found their experience worthwhile.

“Nothing did more conduce to recovery than Experience, wherein we finde the most learned Doctors often overcome, by silly Country old women, one of which has done better with one single Herb or Plant, than the most famous Doctors, with all their most elaborate Receipt.”5

The chiurgion George Gifford was not as much of a fan. He wrote scathingly of one old woman who worked on Seacole Lane who “hath more skill in her Colebasket, then iudgement in Vrine (urine), or knowledge in Phisick or Surgery.” 6I am not sure that is the crushing indictment George believed it was, but it does illustrate the tension between the empirics and the Galenists.

I think about that today when I think about how disconnected modern professional medicine can be from suggesting simple, practical advice. I remember telling a doctor I increased my vitamin C to help reduce circulating cortisol in my system. He rolled his eyes at me asking where I learned that and had the good nature to look sheepish when I told him it was on his clinic’s website.

Regardless the old woman’s trade persisted longer than Gifford’s weird urine analysis technique did. Dr. William Withering attributed his “disovery” of digitalis to such a practitioner.

In the year 1775, my opinion was asked concerning a family receipt for the cure of the dropsy. I was told that it had long been kept a secret by an old woman in Shropshire, who had sometimes made cures after the more regular practitioners had failed.7

The single herb cures Agrippa mentioned had been called “simples” dating back to the time of Dioscorides aforementioned work. This led to the use of the name “simplers” for these older women charged with gathering herbs for the townfolk 8 and they enjoyed a brisk trade into the 19th century. Simplers according to 19th century botanist William Curtis acquired their knowledge traditionally and were of the practical sort of botanist “who is capable of naming a plant at sight, but is unacquainted with the names of the several parts which compose it.”9

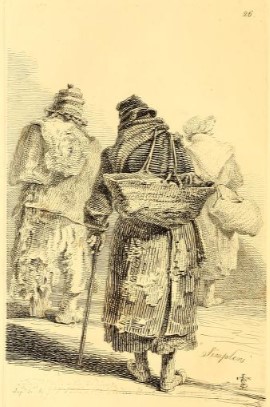

Simplers offered a product that often apothecary shops did not — fresh plants. City dwellers who didn’t have access to rural gardens or foraging, relied on these merchants for fresher ingredients . You can’t pound the juice from dried material. In London, simplers were sure to be seen at the Covent Garden, Fleet, and Newgate Markets.10 Three simplers were depicted by John Thomas Smith in his Cries of London published in 1839.

This serves another example or how our entire understanding of how women lived before the 19th century has been skewed due to the broader problem of traditional knowledge, being dismissed or appropriated. Despite all the earlier works that asserted that the Simplers were “most often women” by the end of the 19th century sources began to state that “wild plants are collected from their respective haunts by men known as Simplers.”11

According to Smith he titled his work from “from a curious half-sheet print, entitled, ” The Cries of London,” to the tune of ” Hark, the merry merry Christ Church bells,” printed and sold at the printing office in Bow Church Yard, London.12It’s interesting to me that thousands of years later after theories have been debunked or reinvented, the Dioscoridian materia medica still shone through in these lyrics.

The industrial revolution changed life in many ways and one was the gradual disappearance of the simplers. While simplers provided fresh, potent ingredients to city dwellers who lacked access to rural gardens, the commercialization of medicine eventually marginalized their role. This marked a shift in how societies interacted with medicinal plants. What was once a deeply personal, community-based exchange was taken on by middlemen.

An 1872 article in the Atlantic Monthly laments, “Among the recollections of my early life is that of the annual appearance of the herb-women — vestiges of the ancient class of simplers, — who earned a livelihood, in part, by gathering and carrying to market herbs, roots, and flowers… The herbs formally gathered by the simplers are now cultivated in garden devoted to this special purpose, belonging chiefly to the Shakers. All romance attending the occupation is destroyed by this change. The herbs are pressed into cakes and sold in the apothecaries shop.”

Industrialization also reshaped the way people interacted with plant medicine, shifting it from individual knowledge and locally grown plants to commodification and mass production. These issues of sustainability still plague the modern commercial herbal complex which has replaced the use of fresh herbs with bags of dried material shipped around the world.

The industrial production of plant-based remedies and mass-marketed dried herbs severely limits many people’s direct connection with fresh plants and produce. All is not entirely lost, though. While not all of us see “herb-women” hawking fresh medicinal plants on the corner anymore, we do see community herbal practitioners, community-based farmers market vendors, and small herb farmers working to revive that connection.

These practitioners maintain the ancient traditions of foraging, cultivating, and using plants directly, resisting the complete commodification of herbal medicine. They serve the role of keeping plant-based remedies accessible to everyone, especially as concerns over sustainability and the ecological impact of large-scale herbal production grow.

References

- Hollman, Arthur. ‘A History of the Gardens of the Royal College of Physicians of London’. Clinical Medicine 9, no. 3 (1 June 2009): 242–46. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.9-3-242. ↩︎

- ‘Samuel Ball Platner, Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, ELEPHAS HERBARIUS’. Accessed 10 May 2020. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0054:entry=elephas-herbarius&highlight=herbarii. ↩︎

- Helmont, Jean Baptiste van. Van Helmont’s Works Containing His Most Excellent Philosophy, Physick, Chirurgery, Anatomy : Translated by Chandler, John. London, England: Printed for Lodowick Lloyd, 1664. ↩︎

- Agrippa, Henry C. The Vanity of Arts and Sciences. Translated by Samuel Speed. 2005th-12 (EEBO-TCP Phase 1). ed. London, England: Printed by J.C., 1676. ↩︎

- Gifford, George. A Discourse of the Subtill Practises of Deuilles by Vvitches and Sorcerers. Imprinted at London: [By T. Orwin] for Toby Cooke, 1587 ↩︎

- Withering, William. An Account of the Foxglove and Some of Its Medical UsesWith Practical Remarks on Dropsy and Other Diseases. Birmingham, England: PRINTED BY M. SWINNEY; FOR G. G. J. and J. Robinson, Paternoster-Row, London, 1785. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/24886. ↩︎

- You might also see them called empirics in some academic literature because they practicised based on experiential knowledge of the generations before them rather than having any particular medical theory. ↩︎

- Curtis, William, and Samuel Curtis. Lectures on Botany: As Delivered to His Pupils. W. Phillips, 1803. ↩︎

- Tuer, Andrew White. Old London Street Cries and the Cries of To-Day: With Heaps of Quaint Cuts Including Hand-Coloured Frontispiece. Published for the Old London Street Company, 1887. ↩︎

- Scoresby-Jackson, R.E. and MacDonald, Angus. Note-Book of Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Edinburgh, Scotland: MacLachlan & Stewart Booksellers to the University, 1871. ↩︎

- Smith, John Thomas. The Cries of London : Exhibiting Several of the Itinerant Traders of Antient and Modern Times. London : J. B. Nichols, 1839. http://archive.org/details/criesoflondonexh00smit. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.