I can’t say no when someone asks me a question, so I will give you one more magic post in honor of spooky month and then we are going to start digging into the practical stuff.

Today we are going to talk about magic in terms of how it was used for healing. I am not here to debate with you the realities of magic. Whether, or not, you believe in such things is not important. What is important is to understand that people who employed these methods believed in their efficacy.

It’s also important to point out that as historians we really only have access to primary source documents about a very small timeframe. So while we might know from Egyptian writing that they venerated cats, we have no way of knowing for certain that they were the first society to do so. Too many historians are guilty of over-attributing certain practices to specific cultures. This approach lacks historical rigor and results in overstating the reach or origin of traditions based on partial evidence.

Let’s not do that.

To begin our post, I want to introduce you to a couple of believers whose views shaped early modern occultism. Roger Bacon and and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa were scientists (in the medieaval sense) and Christians who believed in magic and were for the most part left alone by the authorities. Contrary to popular belief most accusations of witchcraft didn’t occur until the early modern era.

Roger Bacon was born in Ilchester in Somerset, England, in the early 13th century sometime between 1210-1220. Bacon studied at Oxford and his work was clearly influenced by Robert Grosseteste who was one of the first advocates in Western European scientists to the idea of empiricism, which is the the idea that knowledge should come from observation and experimentation rather than solely from authority or tradition. Bacon was the first to employ the empirical method attributed to Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) to Aristotle’s work.

While Bacon was very much a scientist, he was also a practicing alchemist who believed in mixing Hermetic teachings into Christian theology. By the early modern era Bacon had become referred to as Dr. Miribalis and gained the popular reputation of being a magician in possession of the brazen head- a mythical device that could answer questions or predict the future.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa was born centuries later on September 14th, 1486 in Cologne, Agrippa graduated from the University of Cologne in 1502. Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia libri tres (1533) is arguably the most important text in the Western magical tradition. 1 Agrippa merged his devout Christianity with esoteric and Hermetic traditions in a way that defined occultism during the Renaissance.

In De Occulta Philosophia, Agrippa proposes that “Hearbs and other natural things” have different types of properties or virtues including:

- Natural Virtues are properties derived from the elemental components of the plant itself.

- Celestial Virtues are attributed to the planets, stars, and constellations that rule over certain plants and imbue them with certain qualities. In this case sympathetic magic involves choosing plants for a formula whose ruling planet aligns with your desired outcome. Agrippa’s writing on this subject is where Culpeper got his information.

- Occult Virtues relate to using plants in a religious or ritualistic context to invoke divine powers or spirits. The term term occult is derived from the Latin occultare ‘secrete’ and its frequentative occulere ‘conceal’. Agrippa assured his readers that ” their Causes lie hid, and mans intellect cannot in any way reach, and find them out… These “hidden” virtues must be found out by experience.”

- Agrippa believed that the “Spirit of the World” (animus mundi) was responsible for conveying this occult quality into “Hearbs, Stones, Metals, and Animals.” 2 Agrippa believed this explained the influence certain plants had on invocations, prayers, or offerings tying their use to specific forms of ritual magic.

Note that both these men taught within the context of Christianity. Magic persisted in folk practice, too. Leaving votive offerings for saints in return for their blessing and spaces at the table for ancestors continued to be perfectly acceptable. The laying on of hands was also completely normal for English and French Catholics who believed their monarchs had the power to heal scrofula with a touch.

Ronald Hutton has pointed out that medieval religious practices often blurred the lines between religious mysticism what would later be condemned as witchcraft3.

Apotropaic magic

Apotropaic healing magic dates back to the times when people believed that illness was caused by supernatural causes. Early physicians were often considered to have knowledge of magical practices that would repel or ward off disease causing spirits. The term comes from the Greek word “apotropaios,” meaning “to turn away” or “avert.” Hanging mugwort in a home to protect from evil spirits, is an example apotropaic magic, as is hanging mistletoe to keep away the “Night Mare.“

Suffumigation specifically refers to burning plants for their smoke during magical rituals. For example, regardless of their somewhat more rational approach to medicine, even the Greeks still attributed some illnesses to the malevolent spirits. Epilepsy was thought to be the result of being possessed by the demon Lugalurra and there was a complex ritual for exorcising him that ended by fumigating the patient with a sacrificed goat.

According to Agrippa, ” fumes made with Lin-seed, and Flea-bane seed, and roots of Violets, and Parsly, doth make one to fore-see things to come, and doth conduce to prophecying, while “a fume made of Calamint, Peony, Mints, and Palma Christi [castor-oil plant], drives away all evil spirits.” Those of you accustomed to using LLewellynized plant magic tables are going to find that they don’t line up much with historical texts.

What is interesting to me is that studying plants used for these purposes in the context of modern biomedicine reveals that some of them have properties which explain their “natural magick.” For example, medicinal smoke has been studied modernly and been found to reduce the airborne bacteria count in a room. 4

Sympathetic Magic

Sympathetic magic is based on the idea that objects, actions, or beings can influence one another through a hidden connection or “sympathy,” that persisted even from far away.5

Effigy magic: This relies on the idea that actions performed on a representation of something or someone (such as a figurine or image) will affect the actual subject. Leaving votive offerings for a statue of a saint or other holy figure is an example of effigy magic that was accepted as a religious ritual.

Creating a doll that resembles a person and performing actions on it to influence that person is also effigy magic. In Ireland this manifested in the form of the Bridog dolls -which were the little dolls made from straw or corn husk to represent St. Bridget. Singing to the doll and treating it respectfully supposedly enticed the saint to visit your home. In the UK and later the US, it took the form of the poppets which were dolls made of clay, wax, wood, or cloth and they way they were treated was believed to impact the person they represented.

Contagious magic: This is based on the belief that once two objects or beings have been in contact, they retain a connection even after being separated. This type of magic explains how the Bratog Bríde (Bridget’s Mantle) was believed to gain healing powers. It also explains why using an object that was once in contact with a person (like hair or clothing) is thought to influence that individual.

Witch-bottles were another type of sympathetic magic aimed at healing people who were supposedly suffering from curses. The urine of the afflicted would be bottled along with salt and sharp objects in order to inflict pain on the witch repsonsible for the curse6. This was one of counter-magic trick cunning folk might recommend.

In all of these situations sympathetic magic works on the assumption that there are invisible links between objects, people, and forces in nature, and that by manipulating these links, a magician can influence reality.

Natural Magick

This is the term I use for phenomena that can be explained by scientific investigation. As I mentioned in my previous post by the early modern era skepticism about magic was arising. Some authors were already attempting rationalize these beliefs.

I tend to be one of those people myself. For example, while some researchers will say that the idea of using yellow juice from certain roots to cure jaundice is sympathetic magic, I maintain that identifying roots by the color of their juice, or taste, is a crude sort of scientific identification. Modern research has proved that the chemical that causes the yellow pigmentation of these plants, berberine, does in fact have hepatoprotective properties.7

Humans spent 2.5 million years experimenting with plant medicine before writing developed. The first recorded medical systems are the result of milennia of trial and error. This begs the question, did the liver become associated with yellow before or after prehistoric people figured out the connection? Is it magic or a mnemonic? We don’t know—and I won’t twist it into ‘woo’ just to get clicks.

I hope you have enjoyed this very brief summary of how magic was woven into the healthcare culture. People like Roger Bacon and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa weren’t irreligious. They mixed faith, science (as it was understood then), and mysticism into a system they genuinely believed had power.

I tend to focus on the practical methods that are grounded in historical precedent because I believe these remedies still have a lot to teach us. I’ve been thinking that perhaps I could relent on that a little and include a little more estoteric information because it seems to be of interest to a lot of people.

References

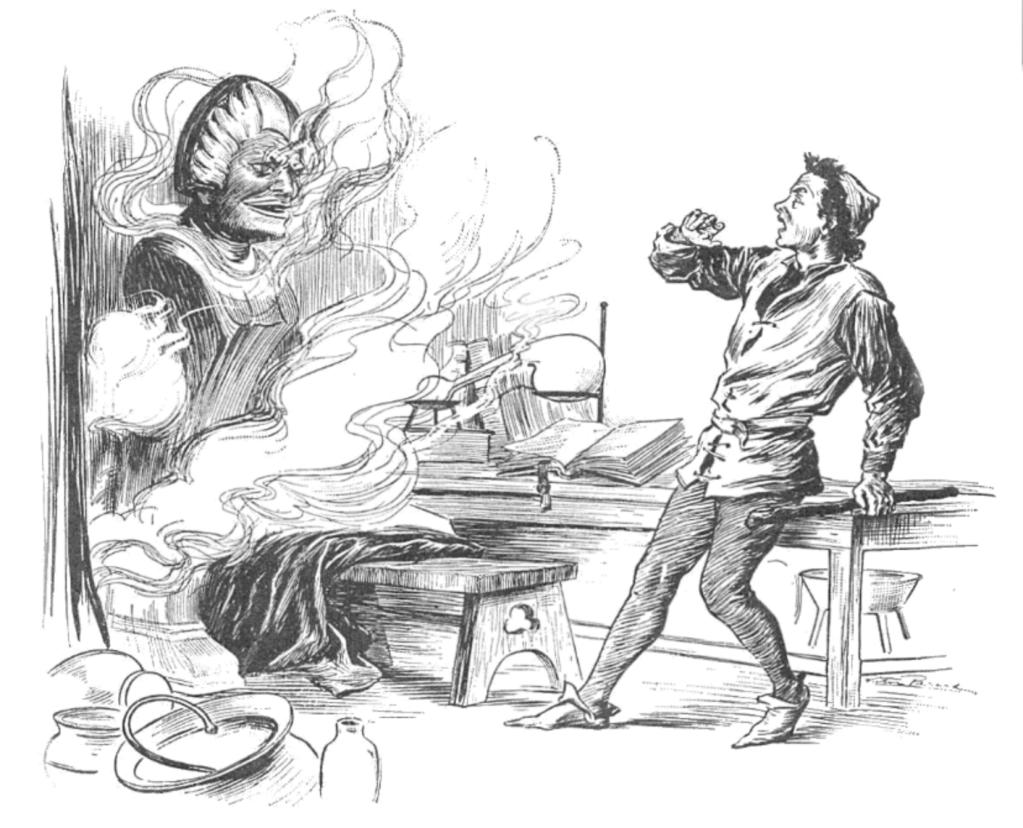

Header image is by French engraver Laurede titled The Night Mare, 1782

- Agrippa, Heinrich Cornelius. Three Books of Occult Philosophy. Translated by Eric Purdue. New York: Inner Traditions, 2021. [This is for modern readers. I use the 1651 translation just to get a feel for how it was interpreted and implemented during the time I tend to study] ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Hutton R. Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015:151. ↩︎

- Nautiyal, Chandra Shekhar, Puneet Singh Chauhan, and Yeshwant Laxman Nene. ‘Medicinal Smoke Reduces Airborne Bacteria’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 114, no. 3 (December 2007): 446–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.08.038. ↩︎

- Hutton R. The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2017:223. ↩︎

- Hutton. Physical Evidcence. ↩︎

- Neag, M. A., Mocan, A., Echeverría, J., Pop, R. M., Bocsan, C. I., Crişan, G., & Buzoianu, A. D. (2018). Berberine: Botanical Occurrence, Traditional Uses, Extraction Methods, and Relevance in Cardiovascular, Metabolic, Hepatic, and Renal Disorders. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00557 & Koperska A, et al. Berberine in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-A Review. Nutrients. 2022 Aug 23;14(17):3459. doi: 10.3390/nu14173459. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.