It’s time to move on to a new series of practical articles on caring for the ill and convalescing and as you know I like to start by giving you a brief A&P lesson like I did with fever and reproduction.

The gastrointestinal (GI) system plays a central role in both sustaining health and supporting recovery during illness. Throughout history, both professional and domestic medical traditions have considered the importance of digestive health when caring for individuals recovering from illness.

Healers, whether trained physicians or family caregivers, understood that the digestive system often becomes compromised during periods of illness. This required supporting the ill and convalescing by changing the types of food eat. We will talk about specific ways to do this in future posts.

Modern understanding of gastrointestinal physiology affirms many of these traditional approaches. Today, we know that stress, diet, and gut flora all significantly affect digestion and overall well-being. As we explore the structure and function of the GI system, it becomes clear in illness and in health, it is as essential to healing now as it was in the past.

When you think about it much of the GI tract is really just a long tube that bulges at the stomach, extending from the esophagus to the anus. Muscles in the walls of this tube contract which aids in the transport of food and waste. We call this peristalsis.

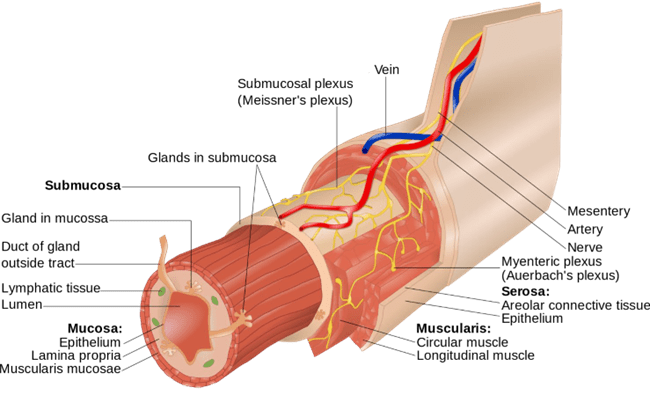

The epithelial tissue is lined by mucous membranes studded with various types of cells. Cells in the membrane include goblet cells (mucous secreting cells), enteroendocrine cells, and bitter taste receptors. The mucosal layer is attached a middle layer called the submucosa that is made up of connective tissue and attached to the outer layer of muscle.

Blood and lymph vessels also run the entire length of the tract, providing nutrition, removing waste and toxins to the liver for processing and transferring assimilated food to the cells via the circulatory system.

The organs of the GI Tract consist of the stomach, the small intestine, and four sections of large intestine. The gallbladder, and exocrine side of the pancreas are sometimes termed auxiliary organs in this system because they contribute bile and pancreatic juices to the digestive process. The mucosal lining of the GI tract extends up the common bile duct to these auxiliary organs.

Stomach

The mucosa that lines your stomach cavity contains glands that produce enzymes and gastric acid known as hydrochloric acid (HCL) and other secretions that help digest food. This musculature of the stomach is responsible for movements that mechanically mix the food with digestive secretions.

The mixture of food and digestive secretions is called chyme. The stomach pushes chyme up into the small intestines through the pyloric sphincter. This is the sphincter that closes when your sympathetic nervous system is triggered. This is why the stress response shuts down proper digestion and assimilation of food.

Small Intestine

You have 25 feet of small intestine. The inner membrane is lined with cells called enterocytes which are absorbent cells covered by about 3000 microvilli. The surface of these microvilli produce peptidases and maltase. The submucosa primarily consists of connective tissue although the ileum contains large groups of aggregated lymph nodules, called Peyer’s patches interspersed in the connective tissue.

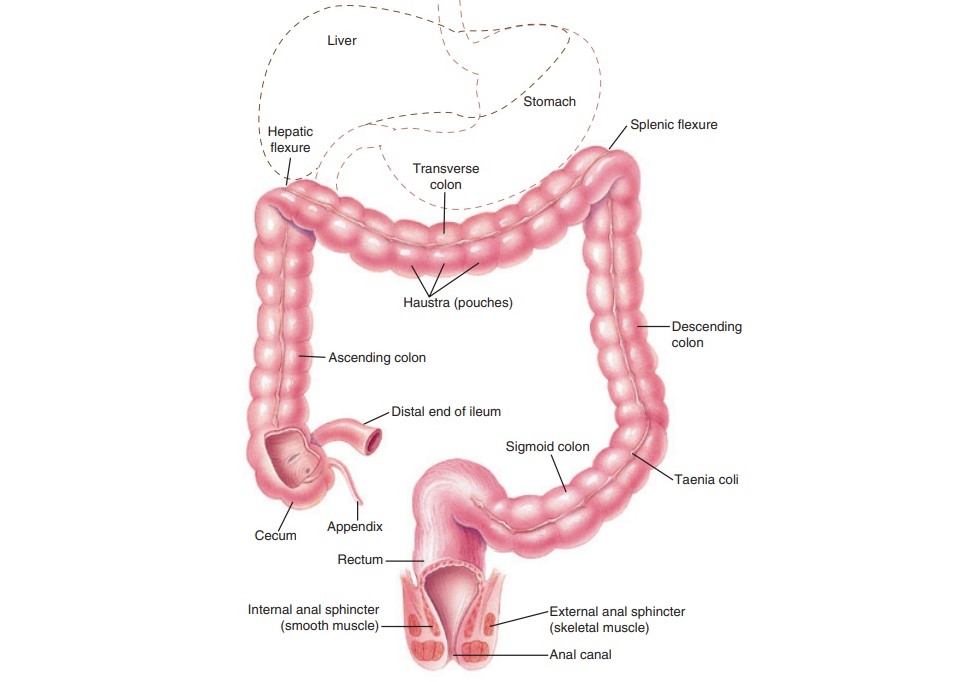

The cecum is a pouch at the junction of the small intestine and large intestine. The ileocecal valve is the sphincter muscle located between the small and large intestine which prevents anything from moving back into the small intestines from the large intestine.

The appendix is at the end of the cecum. Although many people think the appendix is an unnecessary organ, it is important to note that it is comprised almost entirely of lymphoid tissue and functions as a “good safe house for bacteria,” according to Duke surgery professor Bill Parker. “The location of the appendix — just below the normal one-way flow of food and germs in the large intestine is a sort of gut cul-de- sac.5” 1 After an assault occurs, beneficial bacteria housed in the appendix can reseed the GI flora.

Large Intestine (Colon)

The large intestine is the final segment of the gastrointestinal tract, typically about 1.5 meters (5 feet) in length and has a diameter larger than the small intestine. Its primary sections include the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum, each with specialized functions in water absorption, waste formation, and eventual expulsion.

Unlike the small intestine, the large intestine’s mucosa lacks villi, which are finger-like projections that increase surface area for nutrient absorption in the small intestine. Instead, the large intestine has a relatively smooth mucosal surface studded with two types of cells:

- Columnar Absorptive Cells: These cells, also known as enterocytes, facilitate the reabsorption of water and salts, which is critical for maintaining body fluid balance.

- Goblet Cells: Highly abundant in the large intestine, goblet cells produce mucus that not only eases the passage of stool but also acts as a barrier against potentially harmful microorganisms and substances within the fecal matter.

Rectum and Anal Canal: The last 20 cm of the large intestine is the rectum, which serves as a temporary storage site for feces before defecation. The anal canal, at the end of the rectum, contains an internal and an external sphincter. The internal sphincter is under involuntary control, while the external sphincter allows voluntary control over bowel movements, marking the transition from the digestive tract to the outside of the body.

Overall, the structure of the large intestine is optimized not for nutrient absorption like the small intestine is. It’s build for water reabsorption and the formation of solid stool, so any beneficial metabolites have to go through a process to make them liquid-like. That’s where the microbiome comes into play.

Gut flora, or the microbiome, refers to the diverse community of microorganisms that reside primarily in the large intestine, but can also be found on the skin, in the oral cavity, in the lower urogenital tract, and in the upper respiratory system.

The colon contains several pounds of bacteria that live in symbiosis with us. While most bacteria are thought to prefer a slightly alkaline environment, there are those such as acidophilus (acid loving) that hang out in pockets of lower pH in the colon.

We hear about these bacteria frequently but many people aren’t terribly clear on how they are actually helpful. Bacteria in the colon ferment carbohydrates that escape digestion in the small intestine through metabolic processes that break down these complex carbohydrates into simpler, beneficial compounds. In addition to aiding digestion, gut flora is involved in synthesizing essential vitamins like vitamin K and regulating immune function.

Types of Fermentable Compounds

- Insoluble Fiber: Found in grain hulls and plant cell walls, such as cellulose and lignin, this fiber type is more resistant to bacterial breakdown but helps provide bulk to stool, facilitating bowel movements.

- Soluble Fiber: Includes pectins, β-glucans, guar gum, inulin, and oligofructoses, which are easily fermented by gut bacteria and producing beneficial metabolites. In terms of grains, this means that rice, oats, and barley contain fermentable fiber while wheat bran does not.

- Resistant starches are starches that pass through the small intestine undigested. Once they reach the large intestine, these starches act as food, or a substrate, for beneficial bacteria.

Fermentation Process

Gut bacteria release enzymes that hydrolyze (break down) both fibers and resistant starches into simpler molecules. This enzymatic activity produces primarily short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), gases (like hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide), and other beneficial metabolites. The main SCFAs produced during fermentation include:

- Acetate: The most abundant SCFA, which circulates to other body tissues, including muscles, as an energy source.

- Propionate: Absorbed and utilized in the liver, where it contributes to glucose regulation.

- Butyrate: Essential for colon cells (colonocytes), butyrate is a preferred energy source and helps to maintain the health of the intestinal lining, supporting cellular repair and reducing inflammation.

SCFAs help lower the pH of the colon, creating a more acidic environment. This reduced pH inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria, while promoting beneficial bacteria that protect the gut.

Butyrate and other metabolites modulate immune responses, reducing inflammation and reinforcing the gut barrier function, thus preventing potential pathogens from crossing into the bloodstream.

Other Beneficial Metabolites Produced in the Large Intestines

Phenolic Compounds: Certain bacteria can break down polyphenols (antioxidant compounds from plant foods), producing metabolites that may have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, which benefit both the gut and the body as a whole.

Indoles and Tryptophan Derivatives: When bacteria ferment amino acids like tryptophan, they produce compounds like indole-3-propionate (IPA), which can help strengthen the gut barrier and reduce inflammation.

Vitamins: Some gut bacteria produce B vitamins (like B12, B6, and folate) and vitamin K, which are absorbed in the colon and contribute to overall health.

Variability in individual microbiomes, which are influenced by diet and genetics, means that some people may have higher levels of butyrate-producing bacteria, optimizing their use of fibers and resistant starches for gut health. Other people may experience more gas production, which can lead to bloating.

Intestinal microbiota also regulate the production of neurotransmitters, and a balanced microbiome supports the production of neurotransmitters via the enteric nervous system. This system influences mood and behavior through the gut-brain axis,2 so we will end our tour with a brief explanation of that system.

Early in fetal development the neural crest differentiates into the central nervous system and the mass of neural tissue in the gastrointestinal tract known as the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system has its own reflexes and sensory capabilities. It communicates to the brain via the tenth cranial nerve (the vagus nerve).3

When people talk about “gut instincts” they are referring to those instinctive reactions we have to issues of safety which often seem to be perceived first, through a mechanism involving the enteric nervous system and the limbic brain. Similarly feeling “butterflies in your stomach” when nervous is triggered by enteric nervous system action.

You might think this sounds like new age nonsense, but it is something researchers have been talking about for generations. This is from a journal article published in 1907.

“The abdominal brain is not a mere agent of the [cerebral] brain and cord; it receives and generates nerve forces itself; it presides over nutrition. It is the center of life itself. In it are repeated all the physiologic and pathologic manifestations of visceral function — rhythm, absorption, secretion, and nutrition.”4

90 percent of vagal communication flows from the gastrointestinal tract toward the brain.5 Vagal communication regulates heart rate variability (HRV) and activates the parasympathetic nervous system.

Disruptions in gut flora, whether through stress, illness, or dietary changes, can impair these processes, leading to inflammation, malabsorption, and compromised immune defense, highlighting the microbiome’s essential role in gastrointestinal and overall health. So before you you think about drinking large doses of essential oils, remember that one of the first goals of gastrointestinal healing is to get your gut flora in balance- not kill to it all off.

Throughout history, caretakers in both professional and domestic settings have recognized that nourishing and supporting digestion directly impacts the healing process. Today, with our advanced knowledge, we find scientific backing for many traditional practices aimed at protecting and restoring digestive health during illness.

In upcoming articles, we’ll discuss practical strategies to support digestion for those who are ill or recovering, that utilize both modern insights and traditional wisdom to care for the digestive health in a way that supports our overall well-being.

References

- https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/scientists-may-have-found-appendix-s-purpose-flna1c9465137 ↩︎

- Sasselli, Valentina, Vassilis Pachnis, and Alan J. Burns. “The Enteric Nervous System.” Developmental Biology 366, no. 1 (June 2012): 64–73 ↩︎

- Robinson, B. (1907). The adominal and pelvic brain. Hammond, Indiana: Frank S. Betz. ↩︎

- Hadhazy, Adam. (2010). Think Twice: How the Gut’s “Second Brain” Influences Mood and Well-Being. Retrieved September 15, 2015, from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/gut-second-brain/. ↩︎

You must be logged in to post a comment.