As I mentioned on social media on Friday I have had a request to provide some people working on transcription with enough context about humoral pharmacy to make better translations. So I will start by warning you that this is a long, wordy post for a blog. I suppose you are getting used to that from me by now.

Early modern humoral medicine was largely based on theories invented by Greek, Roman and Arabic physicians so in order to get you to the point we can talk about that, we have to cover some background. I will keep this as brief as I can.

The Empirics

Empedocles is said to be the first philosopher [1] to propose that hot, cold, wet, and dry were the roots that made up all things including humans and medicines although it was Aristotle who popularized this theory in his On the Heavens. Aristotle was an empiric who believed that all knowledge was derived from sense perceptions.[2]

Empiric medical practitioners didn’t spend much time theorizing about pathology and physiology. They believed their decisions should be guided by their experience and the accumulated pharmaceutical experience of those who practiced medicine before them. The word empiric is derived from the Greeek ἐμπειρία which means experience. The medicinal agents they worked with had been subjected to millennia of trial-and-error experimentation and found to have observable effects.

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica was an empiric compilation of the pharmacological action of medicines based on previous works such as On Regimen for Acute Disease by Hippocrates and De medicina written by Celsus and contemporary compilations like Historia naturalis written by the Roman polymath Pliny.

In truth, I am not sure why it is more well-known than others because it contains less information. It could be because the Greeks won the little squabble with the Romans over who had the best healthcare system. I consider De medicina to be the superior work.

Empiric treatments were based on the “contraria contrariis curentur” (opposite cures opposite) premise that exists in most ancient medicinal systems. Contraria contrariis are administered with the goal of driving an action that inhibits the progression of a disease by alleviating its symptoms with a cure of an opposite nature which employs the common-sense therapeutic use of ‘heat to cold,’ ‘cold to heat,’ dry to damp and ‘damp to dry.’

It is important to understand that early physicians from many cultures used similar materia medica despite their personal medical theory. These medicines had a history of efficacy, some of which have been confirmed in modern research.[3]

The Dogmatics

The Dogmatics were those who followed Hippocratic theory. Their focus on observation and theory led them to invent a complicated system of medicine based on the supposed existence of bodily fluids called chymos (humors) first described in the Hippocratic work On Nature of Man.

The basis of Hippocratic doctrine was that disease was a result of the accumulation of corrupt humors which were either too watery or congealed. We do not need to study these humors in depth because that physiology is nonsense.

Dogmatists believed when a provider understands the nature of the disease, they can work to eliminate it by using the aforementioned “contraria contrariis curentur” and a second seemingly opposite theory “similia similibus curentur” (like cures like) which relies on the administration of interventions which in some way enable or provoke the proper function of a diseased system.

The two methodologies are not truly in opposition. It is perfectly possible to administer a preparation that contains both types of medicines. I think Hahnemann didn’t have a solid understanding of Greek theory when he invented homeopathy. Hippocratic physicians employed minimal therapeutic measures including:

- Purgatives and emetics.

- Moist heat in the form of topical preparations and baths.

- Kykeon & ptisane (πτισάν) a thin barley gruel.

- Wine decoctions of various herbs and minerals

- Hydromel – a syrupy mixture of honey and water, not to be confused with mead.

- Oxymel – a syrupy mixture of honey, vinegar, and water.

- Venesection (bloodletting)

The theory of these schools of medicine was ancient by the time Soranus (98-138CE) and Galen (129–216CE) studied medicine.

The Methodics

Soranus was the champion of Methodic theory. The Methodics emerged in Alexandria and it is least possible that some older Egyptian medical theory was also represented in this system. Methodics simplified pathology by attributing illness to one of three tissue states:

Status strictus (contracted or tense tissue)

Status laxus (flaccid tissue)

Status mixtus which was a combination of the two.

Their cures were also based on the principle of Contraria contrariis. The word tonic (tonikos) was originally used to refer to preparations that astringed laxity by restoring tonicity (form and function) to tissue and included cooling acidic drinks, red wine, vinegar, decoctions of quinces, and cooling oils.

Laxative referred to preparations that relieved tension thus restoring function. Methodics relied heavily on aromatic diaphoretics, warming oils, warm drinks, cupping, sleep, and exercising to the point of fatigue as means of addressing laxity.

It is important to point out that I have never seen Methodic and Dogmatic theories proposed as working together in primary source documents, but have seen a lot of arguments between the two groups.

Galenic Corpus

Galen was quite outspoken in his disdain for Methodic theory. He wrote that at least Empiric treatments were successful sometimes and that it was preferable to have no theory at all than to follow Methodic theory.

Galen and his followers incorporated some new ideas into Dogmatic theory and expanded on old ones. They believed that illness was driven towards a “crisis” by the body’s natural faculties. This crisis was the turning point at which the body would resolve the illness by driving out morbid humors, through sweating, urination, defecation, or emesis, or by congealing them at a fixed point, resulting in the formation of pustules that resolved.

If the body was weak and unable to effectively initiate the healing process, which he termed “acrisy” the result was prolonged or chronic conditions. Then they would employ interventions such as purgatives and bloodletting or use topical treatments to draw morbid humors to the surface.

Some modern practitioners have misappropriated this idea of a provoking healing crisis to erroneously explain away poor reactions to herbal interventions. This is also where the idea that people need to purge themselves came from. Consequently, we have all of the nonsense cleanses and flushes that you see on the market.

Additionally, Galen proposed a new system of classifying food and medicine based on their qualities and effects on the body, Galen proposed the qualitative properties of medicinal agents (hot, cold, dry, damp) could be sorted into classes (Þe grees). He also classified some plants and foods as temperate, meaning they were a good mixture of these qualitative properties. Olive oil was his favorite oil to use because he considered it well-tempered.

Arabic Innovations

After the fall of the Roman Empire, much of this information was translated into Arabic by Eastern scholars. Chauliac cites “Avicen” as Galen’s interpreter. He is the Arabic physician most often credited for informing medieval medicine because he is the only one most people know, but this is an oversight. Medieval and early modern manuscripts cite numerous Arabic sources and I want to briefly mention several in chronological order

Abu Yuhanna ibn Masawayh [John Mesue, Damascenus] (ca 777–857) was a Persian physician who directed a hospital in Baghdhad and was a court physician. You will also see him credited for several formulas in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis due to the fact that the formulas in the Italian physician Saladino D’ Ascoli’s 1488 Compendium aromatarium were largely based on his al-Qrabādhīn (Book on combined medications)

Not all Arabic physicians took the humoral approach to medicine. The alchemist Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al Razi [Rhazes] (865-925) was particularly critical of Galen’s theory in his work Al Shakook ala Jalinoos (The Doubt on Galen). I would credit Al-Razi as being very influential along with Aristotle on medieval alchemists like Robert Grossteste and Roger Bacon [Dr. Mirabilis].

Abu Qasim Khalaf Ibn Abbas Al Zahrawi [Albucasis] (ca 936-1013) wrote the surgical manuscript Al Tasreef Liman ‘Ajaz ‘Aan Al-Taleef”, (The Clearance of Medical Science For Those Who Can Not Compile It) in 1000 CE.

Abū-ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn-ʿAbdallāh Ibn-Sīnā [Avicenna] (ca. 970–1037) expanded on Galen’s humoral theory and align the expression of the humors with various emotions. in al-Qānūn fī l-ṭibb (The Canon of Medicine) in 1025.

Diyāʾ al-Dīn Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn Aḥmad al-Mālaqī [ Ibn al-Bayṭār] (ca 1197–1248 AD) wrote Al‐Jāmi˒li‐mufradātal‐adwiyawa‐l‐aghdhiya (Compendium of Simple Drugs and Food). This work added hundreds of new plants to the materia medica from places like North Africa, Turkey, and Syria. Because he was an Al-Andalusian contemporary his work influenced the Toledo translators

These Arabic works, along with earlier works, were translated into Latin by the Toledo School of Translators. Eastern and Western knowledge shaped the medicine taught at the Schola Medica Salernitana which was the leading medical school in Europe through the 13th century when the Black Plague slowed the progress of medicinal advances. Salernitan physicians cite Empirics, Methodics, Dogmatics, and Arabic physicians in their treatises, but humoral theory seems to have taken hold.

Humoral Medicine

The theory of medicine as taught at the Salernitan school persisted into the early modern era. Some humoral practitioners followed this blended system of medicine while other “Galenists” worked from older direct translations of Galen’s work. It is worth pointing out that there were also practicing empirics and “chymical” physicians who did not ascribe to humoral theory.

The therapeutic goal of early modern humoral medicine was to cultivate the corpus eraticus or the well-tempered body which gave rise to long lists of temperate items that were considered to be the perfect blend of hot, cold, wet, and dry.

Hot and cold were considered the active qualities while dampness and moisture were considered passive qualities. Some hot medicines were thought to concoct (ripen to the proper state) congealed humors which resulted in them being naturally eliminated from the body. Conversely, they believed cold congealed the humors which had the passive action of either creating moisture or drying up watery discharge.

This was not done indiscriminately. They believed too much heat destroyed moisture and that overuse of cold remedies could congeal moisture to the point of destroying it and creating dryness. Too much dryness was thought to consume vital moisture and natural strength.

Physician William Salmon wrote that the 4th class of dry agents ” dry up the radical moisture, which being exhausted, the Body must needs perish.” His list included: Roots of Pyrethrum, Leeks, Garlick, black and white Hellebore, Gentian, Rue, Seeds of Mustard, Poppie, and all sorts of Pepper.

Medicines that were “out of temper” were considered to have one or more of those qualities in abundance that had a therapeutic effect. Medicines were grouped in classes called þe grees (Lat: the steps) according to those qualitative properties and were mostly categorized by their action on the humors. Some examples include:

- Heating or cutting congealed (unnaturally thick or tough) humors so that they become thin again and could be eliminated naturally.

- Opening obstructions that impeded the proper elimination of humors.

- Expelling wind or morbid vapors collected in the body due to weak digestion or corruption of humors.

- Repercussing (driving out) morbid humors that were thought to cause swelling.

- Drawing morbid humors in pustules to a head so they could resolve naturally.

- Drying watery humors that were said to result in defluxion (fluxes) or rheums (catarrh).

Humoral physiology is as I have mentioned mostly nonsense. I suppose we do have blood and blood channels in our body but I have yet to find a wind channel, and I am fairly certain my uterus does not rise up in my body to keep my diaphragm from working. I find the Methodic theory far more intriguing in terms of modern exploration, due to the ideas about tissue holding tension or becoming lax which we know are indications of modern chronic disease. It is still useful to know what a practitioner meant to accomplish.

I have worked for pharmaceutical companies to comb through old formulas for ideas for new drugs. Of course, they know the physiology was incorrect but acknowledge that there might be a reason that a particular remedy worked, and they investigate what that reason might be.

Sometimes researchers determine that it is a case of correlation mistakenly being construed as causation. Sometimes they find something valid, such as was the case with artemisinin. This approach has led to the development of thousands of pharmaceutical medicines over the centuries.

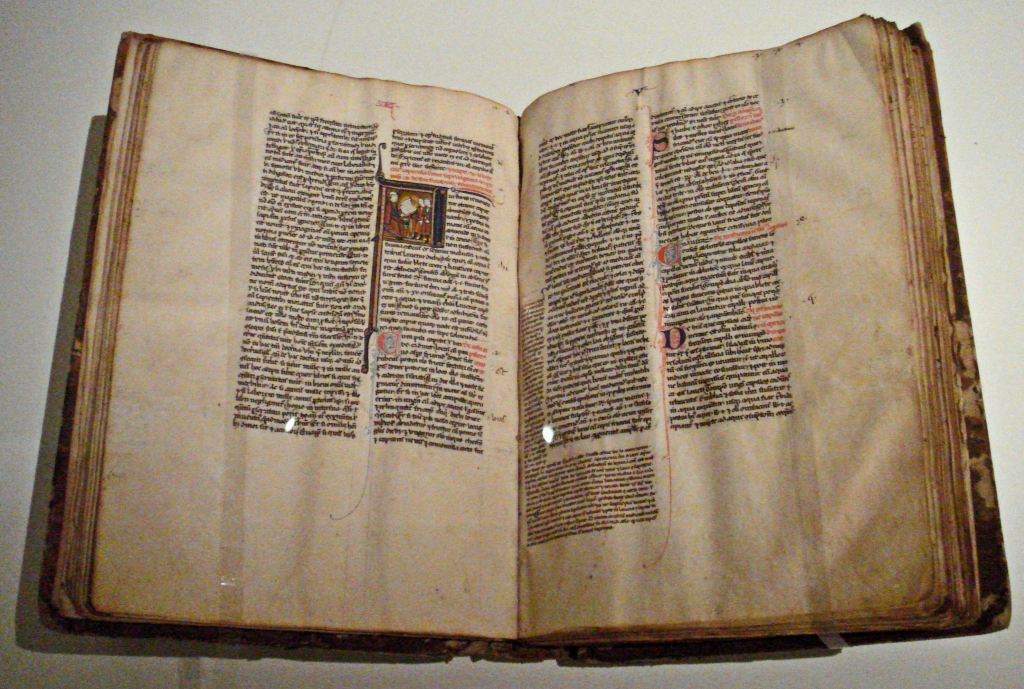

I know that was a lot of exposition just to get to my cheat sheet for helping me to remember, context. It was compiled using several sources including The Cyrurgie of Guy de Chauliac (1363) Lanfrank’s Science of Cirurgie (1396), William Turner’s Herbal (1568), and William Salmon’s Doron Medicum (1683). They of course did not always agree exactly on the categorization of a particular herb but there was enough agreement to give you a few examples.

[1] I hope we all know by now that this just means he’s the first person historians have found to this date, who wrote it down.

[2] I am aware this is a dramatic over-simplification, but it suffices for this discussion.

[3] Yarnell, Eric, and Alain Touwaide. ‘Accuracy of Dioscorides,’ De Materia Medica (First Century C.E.), Regarding Diuretic Activity of Plants’. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 25, no. 1 (January 2019): 107–20.

Nice! Thanks for this.

LikeLike

Just because they don’t talk about theory much doesn’t mean that the original formulas weren’t grounded in humoral theory. But I agree that they were empirics because they mostly cared about results and not how they got there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I think the most important thing this post highlights is that despite what we read about humorism being the dominant theory, there must have been a good deal of dissent. Why would Galen waste his time refuting Methodic theory if it wasn’t competitive? Receipt books seem to be fairly empiric in nature.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We will see how it goes. I can always delete nonsense. I added a few more links. As far as your question in the group, I prefer Beck’s translation of De Materia Medica. The only translation I know about of al-Bayṭār is the French one.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I really appreciate you opening up comments on some of these posts. Thanks for all your hard work on this. I especially appreciate the links to the primary source documents. Can you add more?

LikeLiked by 2 people