Today’s post is going to take a look at how we apply modern science to an old receipt to achieve a safer final product. Since I harvested my black currants last week I thought I would cover that. People who kept receipt books often assumed that everyone had a sort of base knowledge that very few people today have. This very sparse receipt for making black currant jelly is an example of that.

Boil currants with the same amount of water and squeeze out the juice; to every quart, a pound and a half of sugar, boil it quick for about half an hour; when cold, put brandy-paper.1

Brandy-paper refers to the practice of soaking a piece of paper with brandy and laying it on top of the jelly before covering the jar with a bladder, which was how jelly was sealed in the days before paraffin existed.

You may recall that I have talked about black currant tea made from this jelly in a medicinal sense. According to Hannah Glasse, it was strictly a medicinal preparation but I disagree. I made an excellent Bakewell Tart with a jar last fall.

The internet is a sketchy place to learn about preserving. Some folks have been scared to death of canning, and then you have people still sharing recipes that don’t contain much more information that these. I like to think I have arrived at a happy medium. I know that sanitation is important, but I recognize when someone is being overzealous.

For the most part, I defer to the USDA’s Complete Guide to Canning on the National Center for Home Food Preservation’s site, but I am also willing to deviate at times especially when I can’t find something. There is no recipe for black currant jelly in it. This baffles me, but it is what it is.

So today I thought I would share a very detailed recipe for someone who has never made jelly before. I feel pretty safe going on my own because I know a bit about food chemistry. Before I get to that, I wanted to talk a bit about the science of preserving with sugar. If you want to skip all this, feel free to jump to the recipe.

If you boil a solution of 1 part sugar and 1 part water, the water will eventually evaporate and leave you with a thickened solution we call simple syrup. If you recall from my post on making syrups, in order to achieve a shelf stable syrup, we cook our syrups to thread stage 230-235°F.

This works because the temperature you cook your sugar solution to indicates the concentration of sugar present in your solution. 2 If you cook it to thread stage it has a sugar concentration of around 80%, and will keep if you store it in an airtight container. If you just dump one part sugar and one part water together and boil it five minutes, it is most likely going to ferment because there’s too much water in your final product.

Syrup is useful for preserving because like sugar and honey, it is hygroscopic. It ties up water out in preserved foods which spoilage causing microbes need to live. A microbiologist will tell you that at the very least solution needs to 65% sugar for this to work.3 A home economist will tell you that syrup does not help to prevent spoilage, but then turn around and tell you it helps canned food retain its flavor, color, and shape. I think that’s just a CYA thing.

Working with fruit juices is similar. If you cook fruit juice or mashed fruit with sugar long enough, your solution will eventually turn into a thickened substance. Fruit solutions have a bit of an advantage though, because they contain pectin.

Pectin is a polysaccharide that occurs naturally in fruit as they ripen. It is usually concentrated in the skin, cores and sometimes the stems like is the case with currants. When activated pectin forms hydrocolloid networks in your final product. This means that the pectin bonds to itself and creates a thread-like network throughout your solution that holds water and other particles evenly, resulting in a set gel.

This process faces some challenges though.

Some fruits have more pectin than others. Tart apples, crab apples, cranberries, black currants, concord grapes, lemons, limes, plums, gooseberries, and quince will easily gel and are good candidates for making jelly. 4 Other fruits might best be used to make jam. Overly ripe fruits contain less pectin than those that are just beginning to ripen, so picking early is better than late.

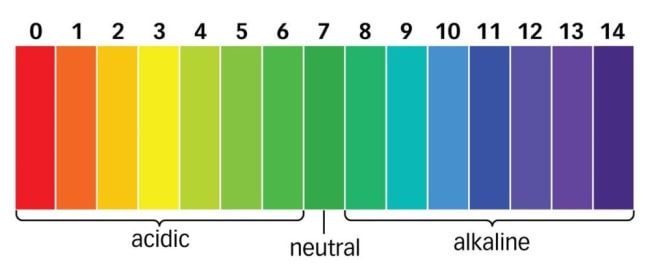

Pectin gels best in substances with a pH of around 1-5.5 The acidity helps to neutralize the sugar-water molecules so the pectin network can surround it. I split the difference and aim for 3 – 3.5. If you go to low, you end up with syneresis, which means water sweats out of your gelled substance. Remember to raise acidity we want to lower the pH

If you are working with commercial pectin or jam sugar, you don’t have to worry about this because they have citric acid added. If you are working without those, you can add lemon juice, white wine vinegar, or citric acid to lower the pH a bit.

Pectin loves to stick to water molecules. In order to get your solution of juice, sugar and acid to gel, you have to convince the pectin to grab hold of itself to create its network. Luckily, water prefers to bond with sugar instead of pectin, so that’s another benefit of using sugar in our jellies and jams. It ties up the water in the solution so that pectin can’t bond with it.

Temperature also activates pectin, in a manner similar to the way it activates starches. They get hot and thicken. The target temperature for activating pectin is between 217-222°F (103-106°C). Sugar solutions have a higher boiling point than water so one way to cook a solution to a higher temperature is to add sugar. We need the extra bump from the sugar to get our solution up to a temperature that activates pectin. It’s also worth pointing out here that your jelly/jam will appear thinner when it is hot and will gel as it cools down.

A lot of times people will tell you that 220°F is the target temperature and that can be really frustrating. The way I make my jams and jellies by adding a bit of extra lemon juice means that it gels perfectly at 215-217°F and it’s kind of hard to get it above that temperature, because pH also influences that. I suggest starting the drop test when you hit 215°F. I keep a stack of pyrex custard cups in the freezer for drop testing. They are less likely to crack than plates or saucers.

When you are checking temperature, be sure to give things a good stir so there are no hot or cold pockets. Usually when you hit the temperature at which your pectin is activated, your solution may foam up. Once you hit that temperature it’s okay turn off the heat and process.

Overcooking jellies and jams isn’t about time, it’s about temperature. If you somehow manage to get your jam or jelly too hot, it may break down those pectin bonds and there’s no way it will set without adding more pectin.

Crystallization happens when the pectin bonds become too strong and then you may see your jelly develop a granular texture. That’s usually because you have used too much sugar and haven’t cooked it sufficiently. I feel like it’s almost impossible for that to happen when you use 75% sugar unless you are working with grape juice. That’s a special subject I will tackle when the grapes are ripe.

To Make Black Currant Jelly

Unlike some people I am not going to tell you what you need to have ready to do this. I am going to tell you to read through the recipe to the end and take notes of what you will need.

- Place your currants in a sauce pan and just barely cover them with water.

- Cook the currants until they are soft. Then you can give them a whir with your immersion blender or mash them.

- Let this cool and then pour through a fine sieve. I will then strain the bits again through butter muslin so I can give them a tight squeeze.

- Test the pH of the juice to make sure it is somewhere in the range of 3.5 – 3. If not, add some lemon juice.

- Heat 4 cups of this juice until it is almost boiling in a sauce pan with a thick bottom and a wide mouth.

- Add 3 cups of sugar and pectin if you are going to use it. If you are using jam sugar, it has the pectin in it. (This is a 0.75:1 ratio. If you want you can use a 1:1 ratio which would be 4 cups of sugar.)

- Simmer this until it reaches at least 217°F and it passes a drop test.

- Once you have to a consistency you like, ladle the jelly into sanitized jars. Don’t leave a lot of head space – 1/4 inch is sufficient.

- With a clean damp rag wipe down the rims of the jars and then put a canning flat and ring on each jar. Screw the rings tight enough to keep the water out. A lot of sites tell you to leave it loose and people leave it too loose and water gets in.

- Place jars on the wire rack in your waterbath canner.

- Cover the jars with hot water. Water must cover jars by 1 to 2 inches.

- Place the lid on your canner and bring the water to a boil.

- Let the water continue to boil. This is called processing. We process black currant jelly for five minutes and then turn off the heat.

- Take the jars out of the canner and put them on a heat safe pad or cutting board. You will hear popping noises as the vacuum created in the jar pulls the flat part of the lid down to seal.

- When they are cool you can test them by pushing lightly on the middle of the lid. If they have sealed, remove the rings. We don’t store canned goods with the rings on.

- Rinse your jars off with hot water and be sure they are clean. Let them air dry.

- When they are dry, label your jar with the content and date.

- Store your jars in a cool, dark place.

- Remember to get it out and use it. Don’t forget that a spoonful is a fine remedy for a sore throat, or makes a very nice “tea” for drinking when you have a cold.

References

- Charlotte Mason (1786) Brandy-paper refers to the practice of soaking a piece of paper with brandy and laying it on top of the jelly before covering the jar with a bladder. ↩︎

- There are alternative pectins on the market designed for using less sugar, however I don’t work with them. It cuts the shelf life in half and low-sugar jellies and jams will go off after being opened in less than two weeks. ↩︎

- Sultana T, Rana J, Chakraborty SR, Das KK, Rahman T, Noor R. Microbiological analysis of common preservatives used in food items and demonstration of their in vitro anti-bacterial activity. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2014;4(6):452-456. doi:10.1016/s2222-1808(14)60605-8 ↩︎

- If you want to test to see if a fruit juice has enough pectin, drop a spoon full of it in some rubbing alcohol. It should form a good solid glob. If it doesn’t, you can look back at my recipe for using apples for their natural pectin. ↩︎

- Onyeaka HN, Nwabor OF. Natural polymers and hydrocolloids application in food. Food Preservation and Safety of Natural Products. Published online 2022:191-206. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-85700-0.00003-4 ↩︎

Black currants make me swoon ❤

LikeLike